Private Label Trade Names on American Pocket Watches: The Non-Magnetic Watch Company: Part 34: Challenge of Positional Adjustment on Palladium Hairsprings

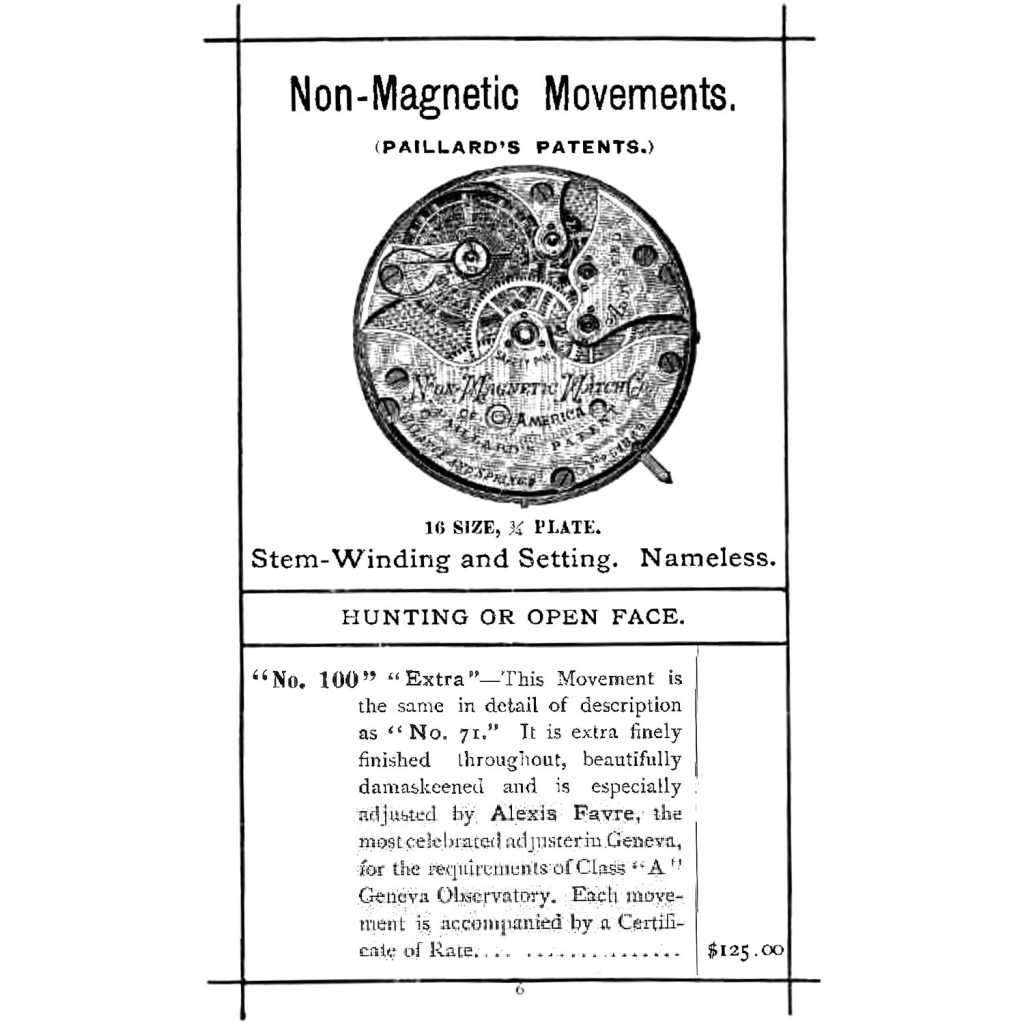

In December 1887, one of the early grade lists was published featuring the available products offered by the Geneva Non-Magnetic Watch Company in America.

While all the movements were adjusted to temperature, one notable difference between the grades described was the level of positional adjustment. The highest quality 20-Jewel movements were adjusted to six positions. The mid-grade 18-Jewel movements were adjusted to four positions. The 16-Jewel and 15-Jewel movements were adjusted to two positions and zero positions, respectively. This disparity emanated from the challenge of adjusting palladium hairsprings to position.

In the 1830s, several decades before Paillard’s development of palladium alloys, John Roger Arnold and Edward John Dent experimented with palladium hairsprings for marine chronometers. Arnold and Dent found the palladium hairsprings to be comparable to steel hairsprings but discovered adjusting the hairsprings to position was a challenge due to the heavier weight.

Mr. A. Hoffer published a letter in the April 1888 issue of The Horological Journal drawing attention to this drawback, especially in relation to ordinary watches like those sold by the Non-Magnetic Watch Company:

“…experiments made fifty-two years ago with palladium springs by Messrs. Arnold and Dent, communicated to the London Royal Society, 12th May 1836, and published in the Bulletin No. 20 de las Classe d’Industrie de la Société des Arts de Genève, clearly showing that English marine chronometer makers had tried a palladium spring before Mr. Paillard was born. Having had myself more first class pocket chronometers provided with palladium springs than with hardened steel springs rated at our Geneva Official Observatory and foreign Observatories, I have come to the conclusion that for the extremes and means of temperature, palladium springs give indisputably as good results as best hardened steel springs, but palladium springs give, on account of their weight, more trouble for the adjusting of the positions than hardened steel springs, which are decidedly more advantageous for watches intended to give very close results in the positions.”Mr. A. Hoffer, April 1888 issue of The Horological Journal

The difficulty and ineffectiveness of adjustment was a constant criticism of the palladium hairspring and balance fitted in watches made by the Geneva Non-Magnetic Watch Company. By May 1888, the company introduced the “No. 100 Extra” grade, masterfully adjusted by Alexis Favre, “the most celebrated adjuster in Geneva, for the requirements of Class “A” Geneva Observatory.” This option demanded a $35.00 premium over the identical Grade No. 71 movement with the same level of adjustment by a different adjuster.