Private Label Trade Names on American Pocket Watches: The Lincoln Watch & Jewelry Company: Part 11: The Practical Effectiveness of the Landis Automatic Regulator

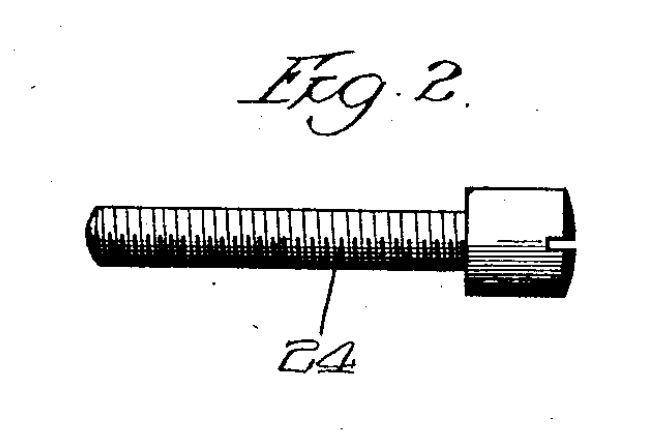

The patent application submitted by Arthur Bonnet in March 1910 for his automatic temperature compensating screw indicates the effectiveness relies on using softer steel with less carbon content.

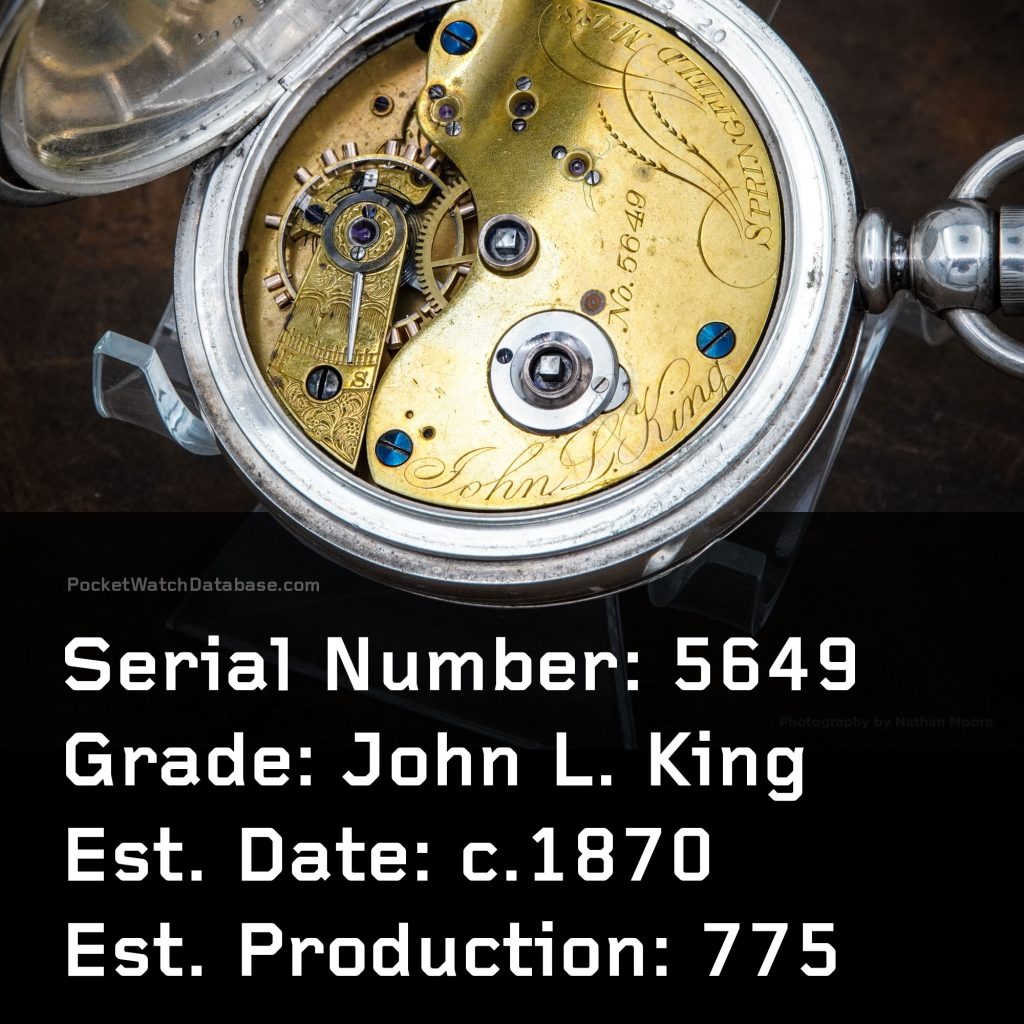

In 1910, Bonnet’s design was implemented on a small number of watches manufactured at the Illinois Watch Company factory for the “Landis Watch Co.” However, this new mechanism may have been nothing more than a marketing scheme to sell more watches by introducing a perceived improvement.

According to Bonnet, the length of the regulator screw would increase in warmer temperatures, pushing the regulator arm and decreasing the effective length of the hairspring (which had also increased in length in response to the higher temperature). Inversely, the length of the regulator screw would decrease in colder temperatures, allowing the regulator arm to move to increase the effective length of the hairspring, compensating for the decreased length of the steel spring.

The standard Illinois regulator screw used on the 16-Size Model 4 and Model 5 measures 5.25mm at approximately 24 degrees Celsius.

The approximate linear expansion coefficient for hardened steel, as used in standard production, is 0.0000124. The contraction of the metal at 0 degrees would result in the total length of the regulator screw shortening to 5.2484mm. The expansion of the metal at 100 degrees would result in a length of 5.2549mm, representing a difference of 0.00651mm from 0 to 100 degrees.

The softer “mild steel” that is considered the essential aspect of Bonnet’s patent regulator screw has an approximate linear expansion coefficient of 0.000011. The contraction of the metal at 0 degrees would result in the total length of the regulator screw shortening to 5.2486mm. The expansion of the metal at 100 degrees would result in a length of 5.2544mm, representing a difference of 0.00577mm from 0 to 100 degrees.

These measurements also account for the entire screw length, which would not fully apply when the screw is fitted to the regulator assembly with only part of the screw applying force on the regulator arm. As a result, the change in position would be even less than the figures above indicate.

From these measurements, we can conclude that the difference between using hardened steel and “mild” steel for the regulator screw is approximately 0.00074mm, and hardened steel actually produces a greater impact on the movement of the regulator arm than the softer steel that Bonnet proposes in his patent application. In both cases, the length differential in response to extreme temperatures is so minute that it would not cause a perceivable difference in the operation of the watch.

It is unclear whether Bonnet and the Landis Watch Company realized this was an ineffective design or not. The Lincoln Watch & Jewelry Co. advertised the improvement in national magazines, but based on the sparse number of surviving examples, the “Landis Automatic Regulator” does not appear to be as successful as the company had hoped.