Photographs Applied to Enamel Watch Dials

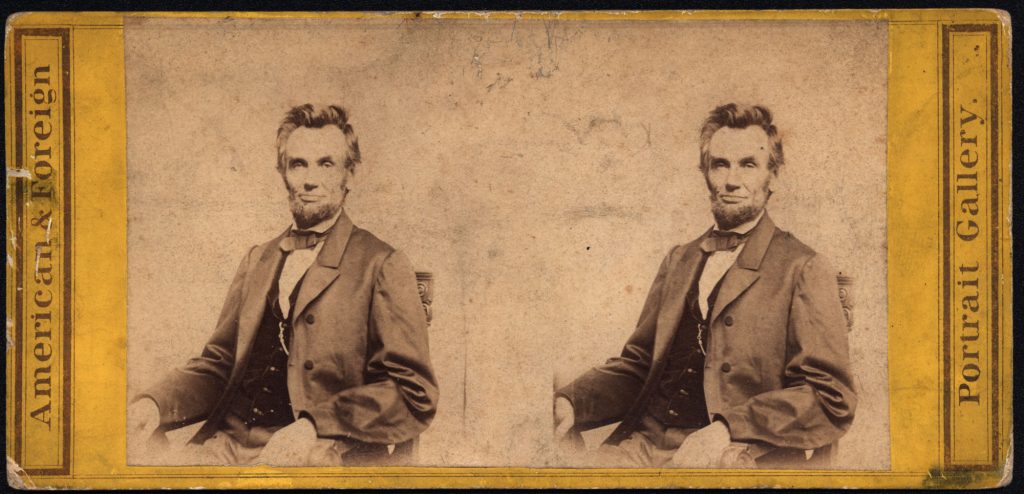

In the 1890s, as photographic techniques were quickly advancing, the practice of placing portraits on enamel watch dials and case caps became extremely popular. Some photography studios even specialized in this form of customization, typically priced at $2-3 per dial or cap (equivalent to approximately $60-90 in today’s economy).

Unfortunately, many examples of this trend have been lost of time due to the delicate nature of the transfer process.

The January 1897 issue of The Keystone described one of the the photographic transfer techniques used to apply the photographs:

The present form of hard enamel pictures on dials is said to be produced by a modification of what is called the “powder process,” but, as far as we have been able to ascertain, the technique of the method has never been made public. The “powder” or “dusting in” process is conducted as follows: Prepare a mixture of composed gum of arabic sixty grains, glucose forty-five grains, glycerine ten minims, potassium bichromate thirty grains, distilled water two ounces. Apply gentle heat, to facilitate the mixture. After thorough incorporation, filter and keep in well-corked bottle. It is claimed such solutions are not affected by light until the film is dried; our advice, however, is to conduct all such operations by non-actinic light, that is, light passing through a red or orange medium. A plate of glass, after warning, is coated (by flowing on) with the above solution, and dried in the dark. This drying is one of the most important factors of the process, and should be effected by warm, dry air. When the gum film is dry, it is exposed under a positive to the action of the light for from three to five minutes if sunlight is used, and ten to twenty minutes if diffuse daylight. The coated glass plate is removed from the printing frame in the dark room, and allowed to absorb moisture from the air. The absorption of moisture will be in exact ratio to the action of the light on the prepared bum film. Thus the parts not affected by light will be extremely tacky, which the portions affected by the light will have ceased to be tacky in proportion as they have been affected. If a fine powder like pulverized black-lead be dusted on the surface, such powder will be retained in proportion to the adhesive (tacky) nature of the surface. Any dry pigment in fine powder can be used instead of black lead. For porcelain work, like pictures on watch dials, the dust employed is black enamel ground to an impalpable powder. The excess of coloring matter not held by the tacky surface is brushed away with a soft camel’s-hair brush. A film of plain collodion is now flowed over the powder picture and allowed to dry, after which the collodion film is detached from the glass and well washed, to remove the gum film. The powdered color is now held by the collodion film, which is transferred to the porcelain surface to be decorated, and heated white-hot to fuse the color fast.The Keystone, January 1897