American Innovation: Benjamin Bacons’s Patent Safety Pinion: Improving Merritt Burt’s Design (Part 4)

Around 1869, the National Watch Company (Elgin) faced the reality that the safety pinion used in its watch movements was inherently flawed. As a result, the company was forced to explore options to either improve on the existing design or replace it altogether.

The company had utilized Merritt Burt’s patented safety pinion since it introduced its first movements to the market in 1867. Burt’s safety pinion relied on a threaded nut tightened atop a hollowed pinion on the center wheel arbor. When the mainspring broke, the force would immediately loosen the nut and allow the pinion to spin freely until the energy was safely expelled.

While the design was effective in loosening the pinion under sudden force, it was discovered that if the nut was not tightened with sufficient torque, it would slip during normal operation. This was originally intended to be a feature of the design, allowing excess force to be released if the watch was wound tightly. However, this feature became a liability as customers began to find that the pinion was unintentionally slipping.

In contrast, if the nut was tightened too much, the pinion would not rotate when the mainspring broke, essentially rendering the “safety pinion” useless.

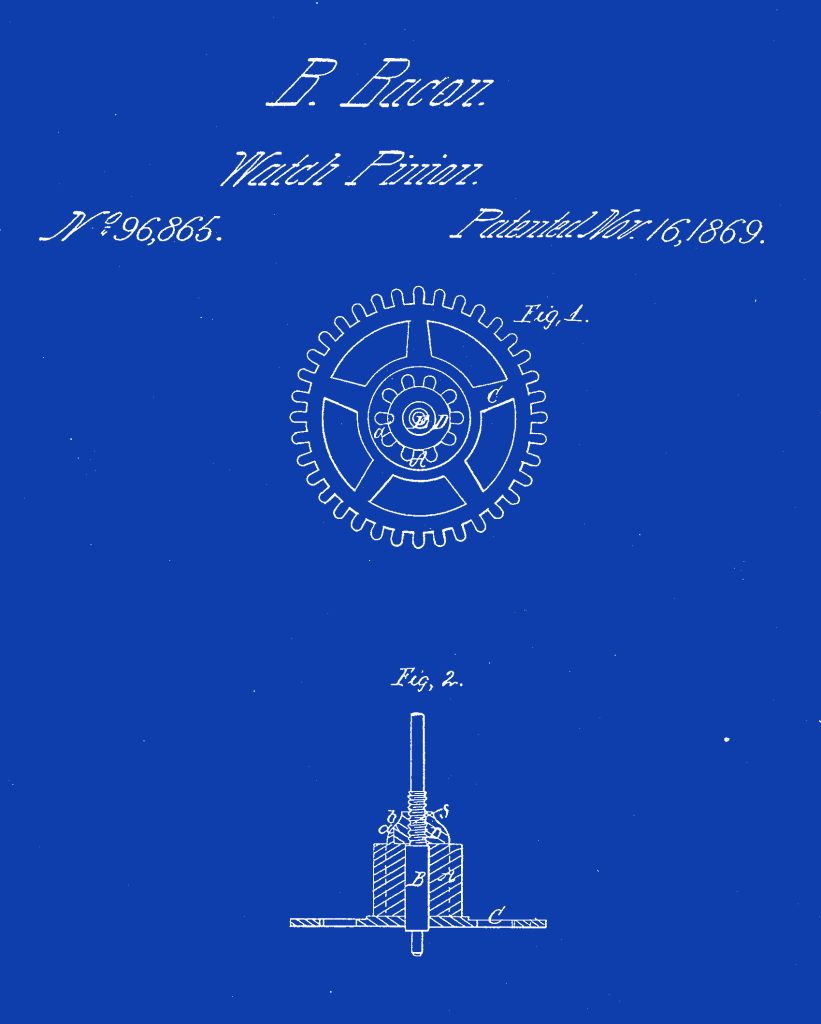

On November 16, 1869, Benjamin H. Bacon secured a patent for a safety pinion design and immediately assigned the patent to the National Watch Company.

The design offered an improvement to address the flaws in Burt’s design by adding a protruding pin to couple the nut to the pinion. This approach prevented the pinion from slipping and still allowed the pinion to loosen when the mainspring inevitably broke. When coupled, the safety pinion operated similarly to the patented design by Charles W. Fogg used in Waltham watches.

Bacon addressed the benefit of his improvement in the patent application, referencing the designs offered by Burt and Fogg (but only directly addressing the objections to Burt’s design).

“This mode of applying the pinion is much better than by securing the pinion on the shaft [Reference to Fogg’s Design], or by holding the pinion by friction alone [Reference to Burt’s Design], both of which modes of applying the pinion are objectionable, as well as uncertain.

Where there is only a nut, it has to be screwed so tight to hold the pinion from turning when the power of the spring is upon it, that there is danger of the back-action, when the spring breaks, of its breaking the pinion before the nut can turn back and loosen the pinion; whereas, with my improvement, the nut being connected with the loose pinion, such nut does not have to be screwed tight at all, but the power of the main-spring screws it up when the power is applied, or the watch wound up. In this case it will be seen that the pinion is perfectly loose, and the least back-action will unscrew the nut and pinion, and the latter will be perfectly loose, but still they are both in their place again when the watch is wound up. This is not so with the nut alone, for when the nut is loosened by the back-action, the pinion remains loose, and the watch has to be taken in pieces, and the nut screwed up again.

Should a person or a watchmaker be not perfectly well posted as to how tight the nut should be screwed up, he may screw it so tight that the back-action will not turn the nut, in which case the nut is of no avail whatever, the pinion then being liable to break by the back-action just as much as if there were no loose pinion. This pinion might as well be fastened to the arbor, as to have a nut that is screwed so tight that it will not turn. With my improvement, the pinion will always turn when there is back-action.” U.S. Patent #96865

Bacon claimed another benefit of his design was that the center pinion would “reset” itself automatically once the watch was wound again, preventing the need to disassemble the movement.

While Bacon’s patent was assigned to the National Watch Company (Elgin), it is uncertain whether this safety pinion was ever implemented into production. In the summer of 1870, Charles S. Moseley, superintendent of the Elgin factory, patented his own improved safety pinion design less than a year after Bacon secured his patent. It is Moseley’s design that appears to be the successor to Burt’s patented safety pinion instead of Bacon’s design.

Inspecting a handful of surviving examples from the production period of 1869 to 1871 has revealed designs that can be attributed to Burt or Moseley. No known example has been discovered fitted with a safety pinion consistent with Bacon’s patented design.

If you happen to come across an Elgin movement with Bacon’s patented center pinion, please let us know.

Nathan. Interesting and informative. I have not done any extensive research but have never seen written reference tio proper service and setting of a safety pinion. Having serviced hundreds of watches i wonder how many have safety pinions frozen on the arbor. Since the beginning of you article i have paid attention to freeing and then allowing the pinion to lock with winding rather than force of hand tightening. I hope you address this issue with your readers. Joe.