American Innovation: Merritt Burt’s Safety Pinion: Introduction (Part 1)

“Mainspring Events”

The large mainspring that serves as the power source for a mechanical watch movement can also become a violent adversary when it breaks, releasing a destructive shock throughout the delicate watch train. As pocket watches became essential accessories, this problem of a mainspring breaking provoked dread among watch owners. Without warning, a single “mainspring event” could render a watch useless, requiring costly repairs or replacement.

When the mainspring in a watch breaks, all the stored energy in the spring is expelled at once like a small explosion, forcefully reversing the mainspring barrel. This powerful shock often damages the pinions, wheels, and jewels if no method is provisioned to absorb the energy safely.

Exploring Solutions

The most clever minds in the watch industry quickly sprung to action to explore solutions to this problem – how to save the delicate parts of the watch when the mainspring inevitably broke.

The most obvious solution, and where many watchmakers began, was to offer adaptations to the barrel design to expel energy safely. While a valid approach, these designs typically required more parts and, thus, increased production costs.

The Safety Pinion

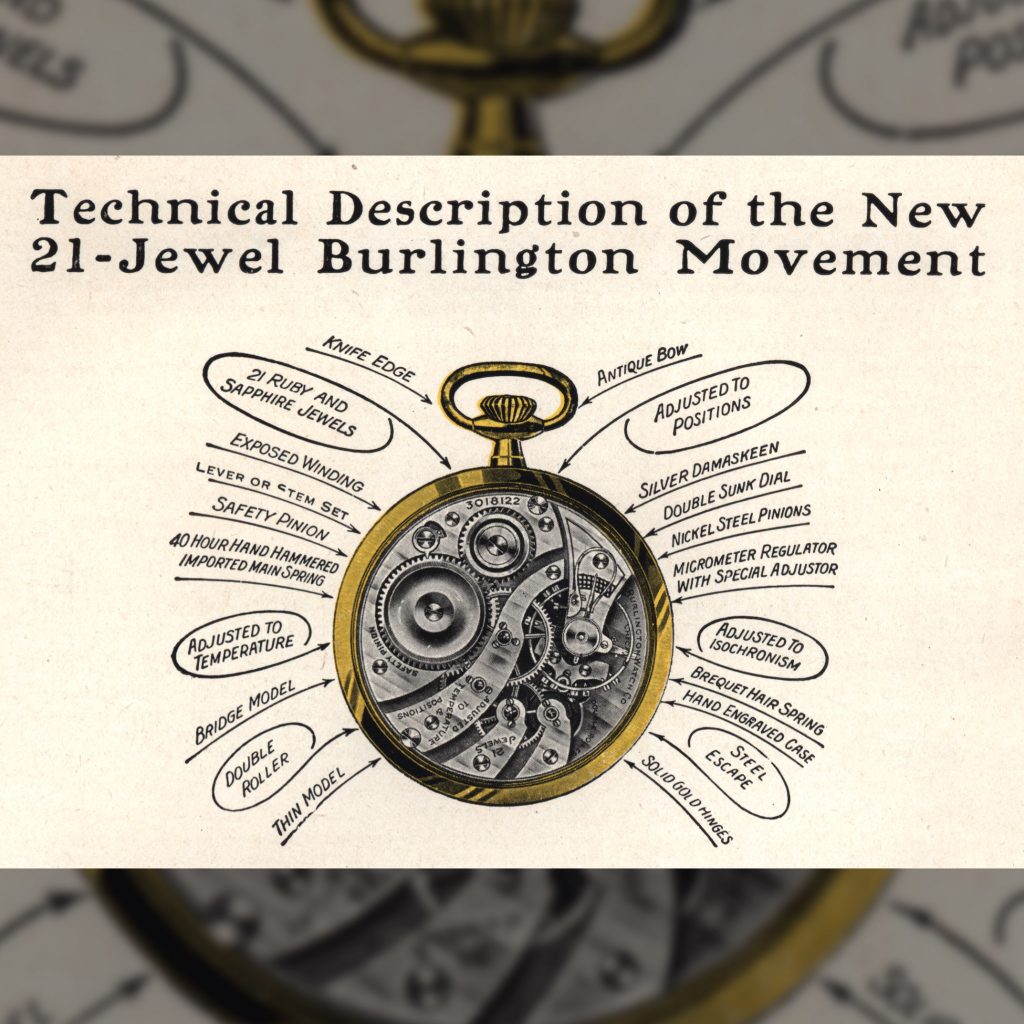

Attention was then directed toward the “first collision” point after the force exits the barrel – the delicate pinion where the barrel teeth mesh with the center wheel. Watchmakers were familiar with this part as a frequent point of failure during a “mainspring event,” often encountering broken pinion teeth. If the center pinion somehow gave way when the mainspring broke, it could redirect the force and prevent the entire train from absorbing the damaging shock.

Burt’s Patented Safety Pinion

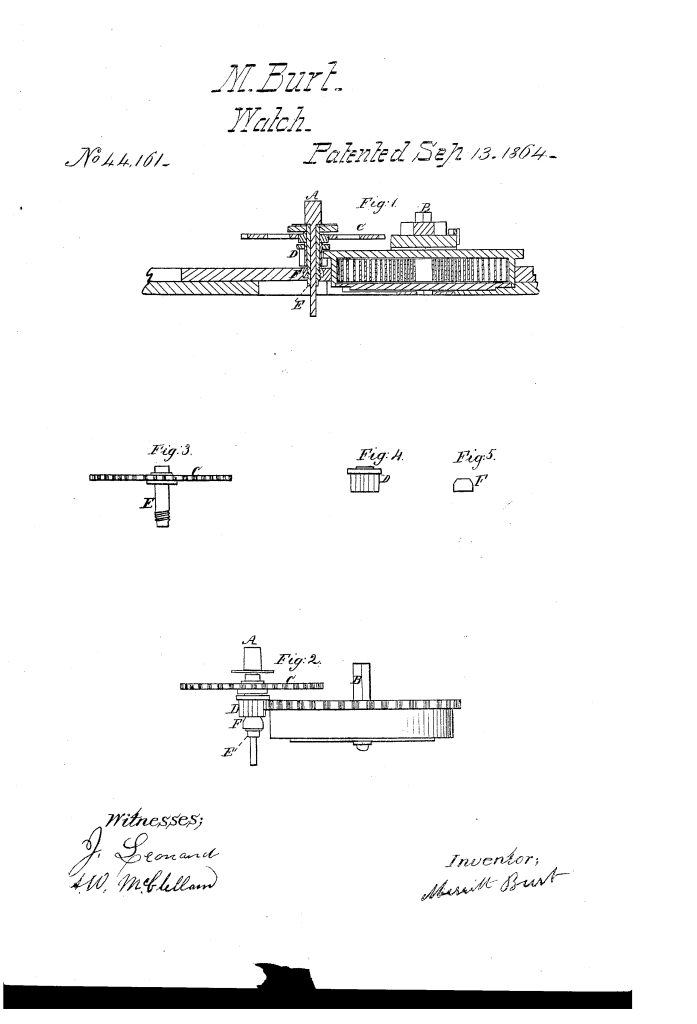

While Charles W. Fogg is often credited with inventing the safety pinion, Merritt Burt first patented the concept on September 13, 1864 – a few months before Fogg secured his own patent.

In Mr. Burt’s patent application, he describes the purpose of his pinion design:

“My improvement, therefore, relates to devices for preventing injury to the train or the usual bad effects which result from the sudden recoil of the mainspring in case of its rupture when wound or partly wound up, and to prevent injury to the teeth of the drum, leaves of the pinions, or any part of the train when would up with too much force.”

The general concept was the same, but the designs were different enough for both patents to be granted patents at the time.

Burt’s patented safety pinion was constructed with a hollow center pinion held in place with friction by a small nut threaded on the center arbor. Fogg’s design was more elegant. The inner part of the center pinion was threaded so it could be tightened directly onto the threaded center arbor. This approach did not require any additional parts, and as a result, the design eventually won more favor in the trade.

Both designs worked by saving the train from the destructive force by allowing the center pinion to quickly loosen when the mainspring broke and the barrel suddenly reversed direction. Burt’s patent also claimed to prevent the watch from being wound too tightly, as the pinion would release excess tension.

The primary benefit of a safety pinion is that no parts are irreversibly damaged. A watchmaker can easily reset the pinion back onto the center arbor, and with a new mainspring, the watch is ready for service again. Since very few parts or adaptations are required to implement a safety pinion, this solution became favored over safety barrel devices that served a similar purpose.

Despite Burt being the first to patent a design for the safety pinion, Fogg’s design was the first to be successfully implemented in production. At the time, Merritt Burt was a watchmaker and jeweler in Cleveland, Ohio, while Fogg was actively employed at the American Watch Company factory in Waltham, Massachusetts. Fogg’s design was intentionally developed for immediate implementation in Waltham watches.

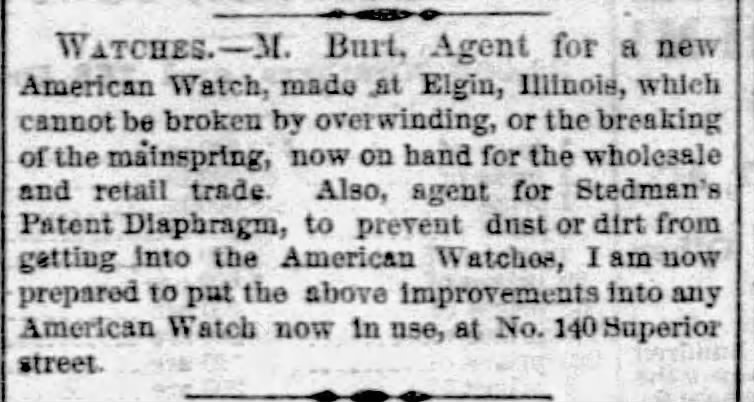

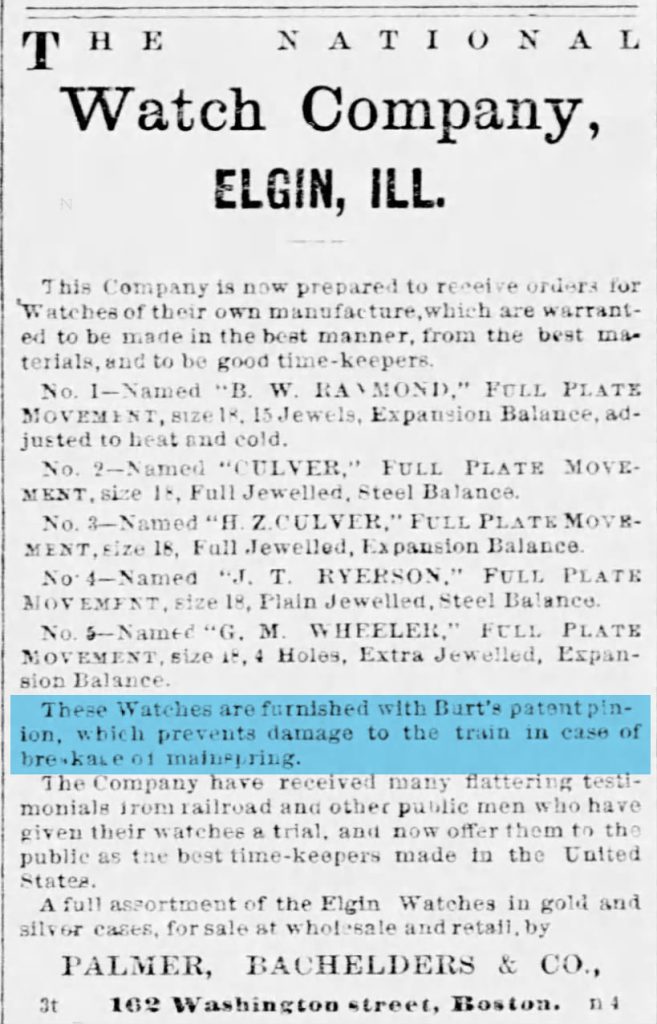

The National Watch Company

When Burt received the patent for his design in late 1864, plans were already underway in Illinois to organize the National Watch Company (Elgin). It is unclear how Mr. Burt became associated with the new company, but when Elgin watches were introduced in 1867, Burt’s safety pinion was a flagship feature. Burt had connections with the railroads in Ohio, possibly resulting in relationships with the leadership at Elgin, as many were also tied to the railroad industry.

Cleveland, Ohio

Thu, Jul 11, 1867

The National Watch Company advertised Burt’s patent pinion as one of the many improvements included in Elgin watches, allowing the company to securely position itself against the products offered by the American Watch Company.

Boston, Massachusetts

Wed, Nov 4, 1868

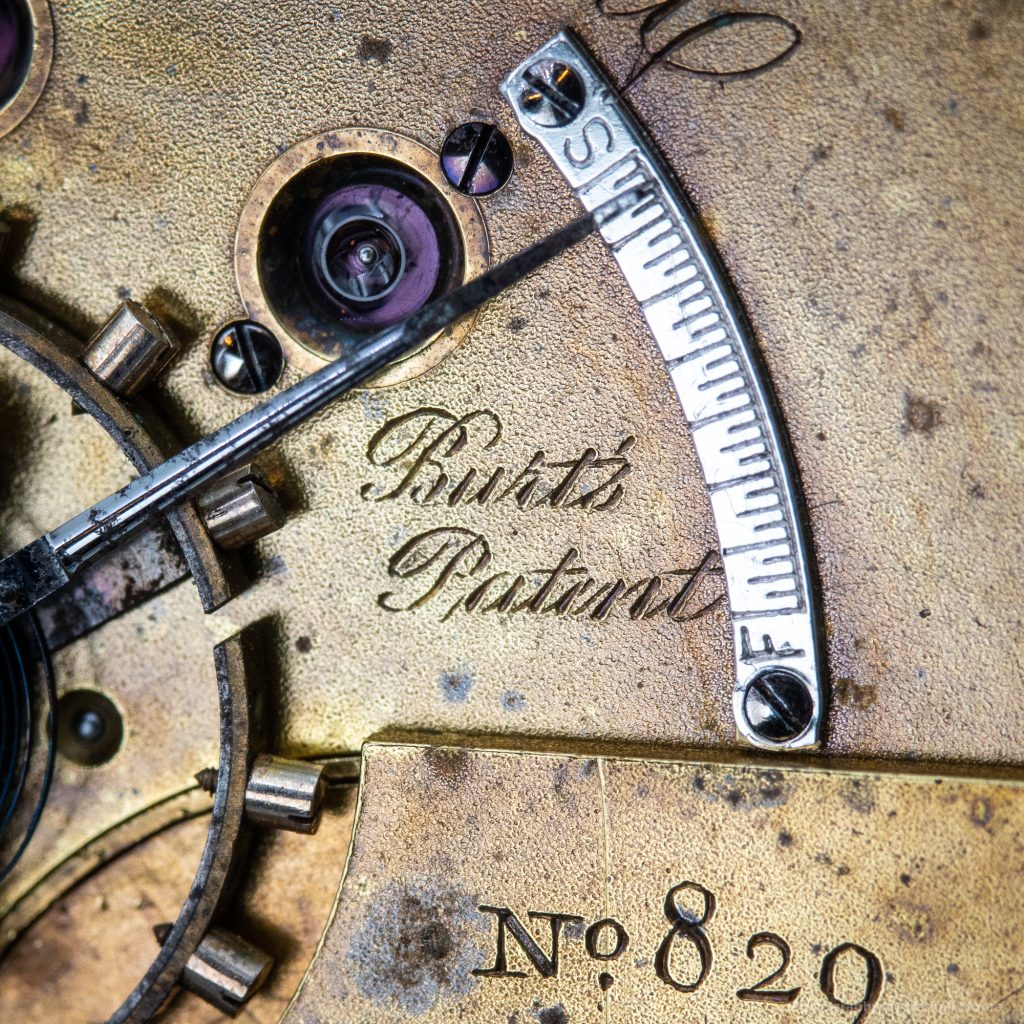

Movement Markings

Early B.W. Raymond movements were prominently marked “Burt’s Patent” underneath the regulator arm. Additionally, the underneath side of the top plate was marked “Burt’s Pat” and the patent date “Sept. 13 ’64.” Other grades were also fitted with Burt’s safety pinion even though they were not directly identified with prominent markings. These movements were simply marked “Patent” on the top plate but still retained the patent marking under the top plate.

The “Burt’s Patent” marking on the B.W. Raymond grade was discontinued around 1868 (Approximately Serial #19,500 – Run 4 of 24). After that point, Raymond movements were marked “Patent Pinion” even though Burt’s pinion was still being utilized.

Discontinued

Around 1871, the National Watch Company (Elgin) was forced to acknowledge that Burt’s safety pinion design was fundamentally flawed.

First, the nut securing the pinion was required to be installed with a certain amount of torque to be effective. If the nut was too loose, the pinion would slip when the watch was wound, and a watchmaker would be required to reset the pinion and nut. If the nut was installed too tightly, the pinion essentially was no better than a rigid pinion, as the force from a mainspring event would break the pinion teeth quicker than the nut could be loosened.

Additionally, over time, the metal surface on the top part of the pinion would burnish the metal on the bottom of the pinion nut, making installation more difficult to achieve with the critical force.

These problems eventually forced the company to discontinue Burt’s pinion in favor of an improved safety pinion design.

Collectibility

Approximately 2,800 B.W. Raymond movements were produced with the “Burt’s Patent” marking, making these movements more collectible than standard B.W. Raymond movements.

Since most Elgin movements produced before c.1871 feature a variation of Burt’s Safety Pinion, movements without the “Burt’s Patent” marking are no more collectible than other Elgin movements manufactured during this era.

5 Comments