Policing the Case Back: The 1908 Stamping Fight and the 1924 Stamping Reform

The 1908 Battle for Time Warranties

After the successful passage of the National Stamping Act in 1906, the watch industry aspired to extend regulation to prevent deceptive practices. While the law established standards for the industry, many felt it did not go far enough.

The Keystone, May 1908

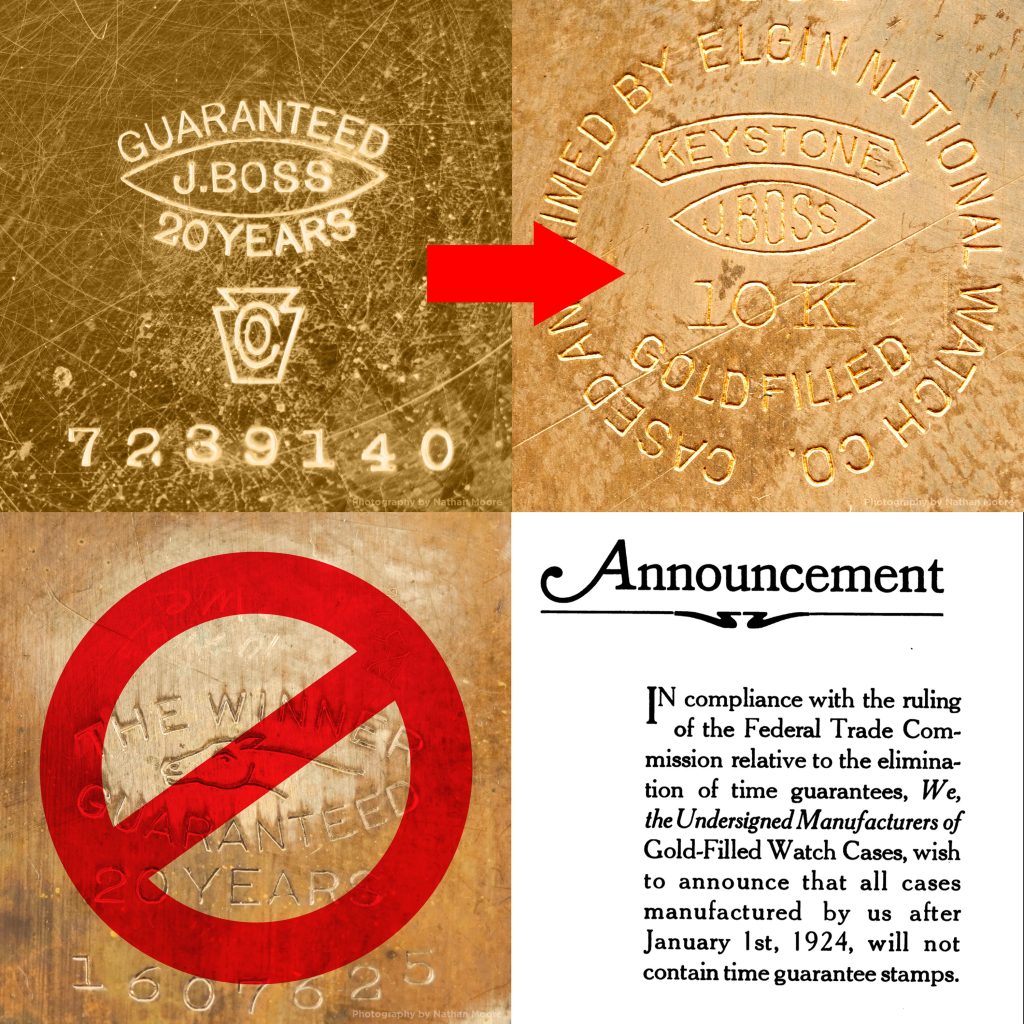

In 1908, building on momentum from the 1906 Act, Rep. Edward B. Vreeland introduced a bill to prohibit stamped time guarantees on gold-layered cases (gold-filled, rolled gold plate, electroplate) and, when a fineness mark is used, require nearby composition wording and the decimal thicknesses of the exterior and interior gold layers (exterior listed first; least thickness if non-uniform). If no fineness mark appears, these disclosures are not required.

Despite early momentum, the bill attracted public opposition from two of the largest watch case manufacturers: Wadsworth and Fahys.

The Wadsworth Watch Case Company published an advertisement in The Jewelers’ Circular-Weekly opposing the Vreeland bill and urging support for a revised bill that would mandate more transparent markings on watch cases.

The Jewelers’ Circular, May 6, 1908

Fahys also advertised their opposition, questioning the true motivation for the bill.

“No Bill is presented to Congress without some interested parties being behind it. Who are the “interested” parties in this Bill? No reputable manufacturer should be afraid to guarantee his product, and no manufacturer who knows his goods are honestly made should be afraid to guarantee the life of their wearing quality, if sufficient gold is used to insure such guarantee.”

The Jewelers’ Circular, May 13, 1908

Not all of the major watch case companies were in opposition, however. The Keystone Watch Case Company publicly supported the act, claiming the bill would help weed out deception in the industry.

The Keystone, April 1908

Despite garnering some support in the industry, there was enough backlash that the Vreeland bill died in committee before making it to a vote in Congress. Interestingly, less than 20 years later, both Wadsworth and Fahys reversed their stance and were among the companies that led a petition to ban the use of time warranties on watch cases.

Change of Tune: Time Warranties Are Scrutinized Again

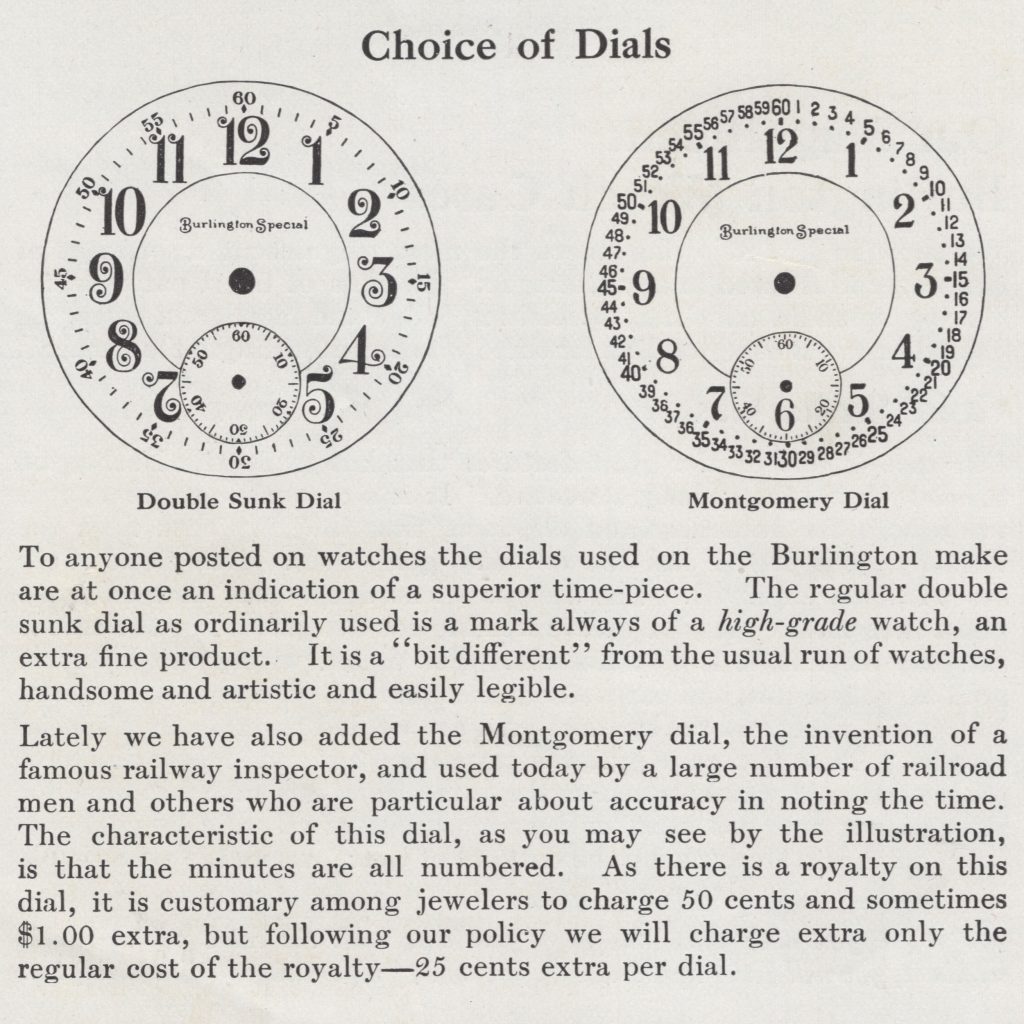

In 1923, as the problem of baseless time warranties on cheap cases became a larger problem, several of the largest watch case companies in the United States partnered to petition the FTC to further regulate the markings on gold-layered cases.

Most modern interpretations of the FTC’s response to the 1923 petition incorrectly suggest that the FTC banned year-based guarantees. However, this is not true. While the case companies specifically petitioned the FTC to prohibit time-based guarantees on watch cases due to some deceptive practices in the market, the FTC did not explicitly ban the practice. Instead, the FTC agreed that certain marks could be misleading and outlined a set of requirements for manufacturers producing gold-filled watch cases, mostly derived from the recommendations of the case companies.

Since the FTC did not explicitly ban the year-based guarantees, the major case companies banded together to force the practice out of the industry starting January 1, 1924. This agreement resulted in the famous announcement published in the December 26, 1923 issue of The Jewelers’ Circular, framed as “in compliance with the ruling of the Federal Trade Commission relative to the elimination of time guarantees…” The verbiage in the announcement implied the FTC had outlawed the practice even though this was not the case (if they had, no collaborative notice would have been necessary).

Because the industry voluntarily changed the marking habits and made it well known in the industry, companies that were intentionally misleading the public were forced to adhere to the adopted standard. This benefited the larger watch companies and eventually suppressed the deceptive companies.

The FTC Ruling & Industry Implications

The following paragraphs provide the ruling submitted by the FTC in response to the petition with my commentary regarding how the regulation would have changed industry practices.

I. That the Federal Trade Commission has reason to believe from the facts submitted to it by the manufacturers, subject to further inquiry in proceedings, as provided by section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission act : (a) That the practice of placing the guaranties on gold-filled and gold-plated watches, for distribution and sale in interstate commerce, has led and leads to deception of the purchasing public. (b) That the marking and/or calling of watch cases for distribution and sale in interstate commerce, as gold-filled, leads to deception of the purchasing public, in the absence of the following elements as a minimum :

This section acknowledges the possibility of deceptive time-based warranties on watch cases. However, it does not ban them outright. Rather, it begins to outline stipulations for gold-filled cases sold in the United States.

(1) That they are marked in close proximity to the words “gold-filled” and as plainly as the words “gold-filled,” with words or marks indicating the fineness of the gold which shall not be less by more than three one-thousandths part than the fineness indicated.

This standard expanded the requirements from the National Stamping Act of 1906 and mandated that the gold purity used for layers of gold-filled cases be stamped plainly on the case. Before this requirement, case manufacturers were only required to mark the case with the composition type (i.e., “gold filled”) if they included the purity mark on the case, as dictated by the National Stamping Act of 1906. However, many manufacturers opted to omit the purity marking altogether to circumvent the requirement to mark the case “gold filled,” or “rolled gold plate,” etc. The standard from the FTC required the purity and the composition to be clearly marked for any case marked “gold-filled,” the fineness must appear next to and as plainly as “gold-filled,” within 0.003 parts of the stated fineness.

(2) That the backs and caps are made of two sheets of gold or an alloy thereof, affixed to the surfaces of a sheet of other metal.

This standard stipulated that if a case company was selling the case as “gold filled,” the backs and caps were required to be composed of a three-layer process, with a sheet of gold on the outer sides with a composition material sandwiched in between.

(3) The center, bezel, pendant, crown, and bow are made of one sheet of gold or an alloy thereof, applied to the outer surface of a sheet of other metal.

This further required the other parts of the watch case to be composed from a two-layer laminated sheet. It was less important to require a three-layer material for these parts because there is only a single “wear” layer, contrasting the dual wear surfaces of the caps and lids.

II. That the commission received the following as the opinion of the trade on the subjects covered, and will take due notice thereof when proper to do so in any proceeding pending before it :

(a) That manufacturers and dealers should be required to place the maker’s trademark “conspicuously and indelibly” on the inner surface of the lid or cap.

This standard recommended the case manufacturer to stamp the company name or other recognized trademark inside the inner surface of the lid or cap, prohibiting “anonymous” watch cases. This forced accountability for all watch case manufacturers.

(b) The sheet of gold or of its alloy affixed to the outer surface of the backs, center, open-faced bezel, pendant, crown, and bow shall not be less than three onethousandths of 1 inch in thickness; the sheets of gold or its alloy affixed to the inner surfaces of the backs, to the inner and outer surfaces of the caps, and to the outer surface of the hunting bezel, shall not be less than one one-thousandth of an inch in thickness.

This standard further established recommendations for the thickness of gold used for gold-filled cases – 0.003 of an inch for outer wear surfaces and 0.001 of an inch for inner wear surfaces..

(c) That whenever the thickness of the sheets of gold or its alloy in gold-filled watch cases is indicated, the mark indicating such thick ness shall only refer to the thickness of the sheets of gold or its alloy so affixed to the outer surfaces of the backs, center, open face, bezel, pendant, crown, and bow, the mark accurately indicating such thickness which shall be expressed in decimals indicating thousandths of an inch, in tests to ascertain the thickness, measurements being taken at a point where no gold has been added or taken away for decoration or ornament.

This standard recommended that case makers only state the thickness of the gold layer when asserting any measurement. However, this was not a practice that was implemented in the watch industry. As a result, this regulation had little impact on the industry.

The Watch Case Industry Evolves Practices

In summary, after the FTC standards were established, watch case manufacturers were held to the following standards:

Required as a Minimum and Enforceable Under Section 5 of the FTC Act:

- “Gold-Filled” Means Gold-Filled – Cases sold as “Gold-Filled” were required to be constructed of a three-layer sheet for caps and lids.

- Mandatory Gold Purity Stamp – The fineness of gold was required to be stamped with the case composition type for gold-layered cases.

Recommended by the FTC, Not Enforceable but Contextually Evaluated During Complaints:

- Company Name or Trademark – The company name or trademark was recommended to be stamped inside the case for clear manufacturer identification.

- Gold Thickness Standard – The thickness of gold used for the case was recommended to be at least 0.003″ thick for outer surfaces and 0.001″ for inner surfaces.

- Measurement Marking Guidelines – If a thickness measurement is stamped, it was recommended that this only reference the gold layer.

Voluntary Industry Self-Regulation:

- No More Time Guarantees – No guarantees stamped on watch cases (voluntary self-regulation, not explicitly prohibited by the FTC standards).

The adoption of these standards by the FTC had a major influence on the American watch case industry. The forced change in marking habits also provides an identifier for modern collectors to estimate the production date of their watch cases. If the case features a year-based guarantee, it was manufactured before 1924. However, many cases produced before 1924 do not feature year guarantees, so the inverse rule does not apply.