Policing the Case Back: The FTC Trade-Practice Ban and the End of Time Guarantees for Watch Cases

The National Gold & Silver Stamping Act, passed in 1906, was the most consequential law regulating markings on watch cases in the early 1900s. However, it quickly became apparent that better reform was necessary for the watch case industry.

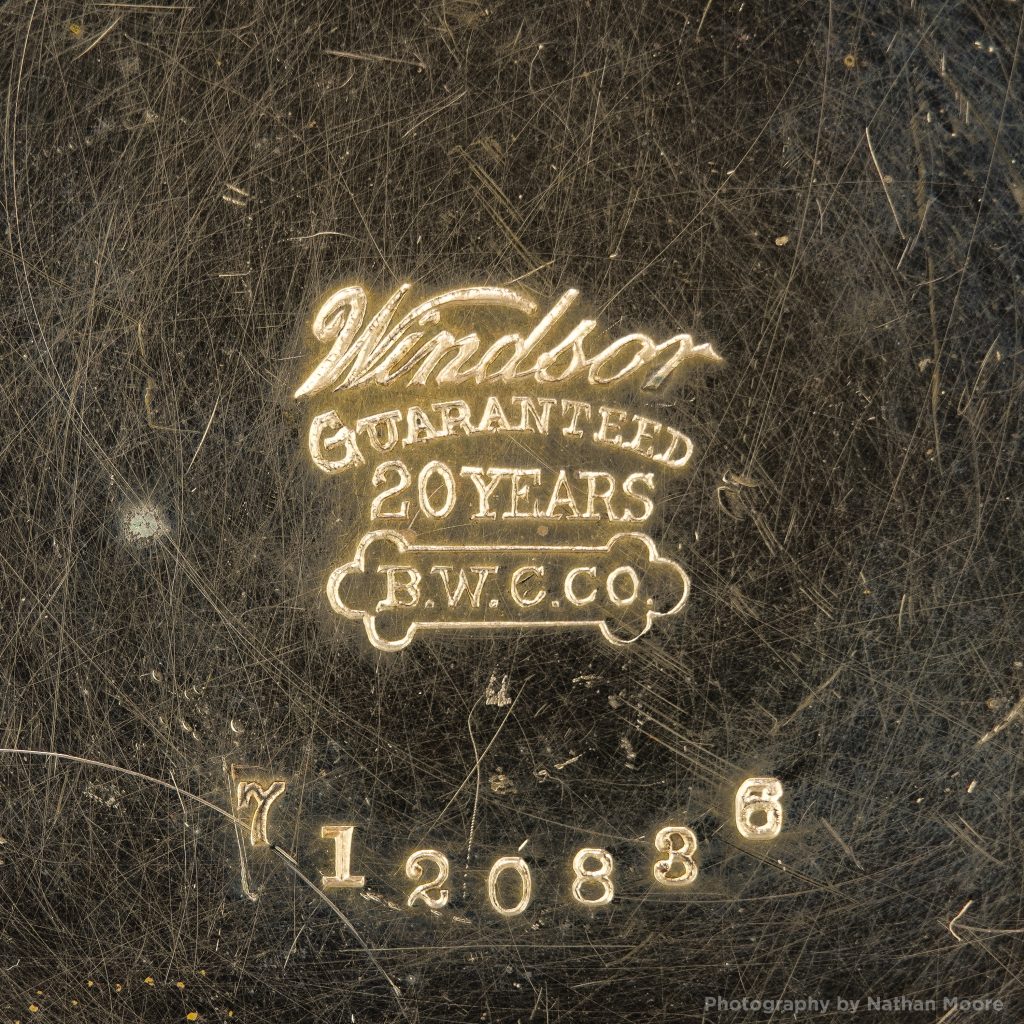

For decades, it became customary and was expected for watch case companies to issue warranties on layered gold cases, including gold-filled, rolled gold plate, and electroplated cases. These guarantees bolstered consumer confidence because the case company would commit to replace any case that wore through to the composition layer within the duration of the guarantee period. While gold-filled cases were more durable compared to solid gold cases, the potential of wearing through to the composition layer was the Achilles heel of these affordable cases.

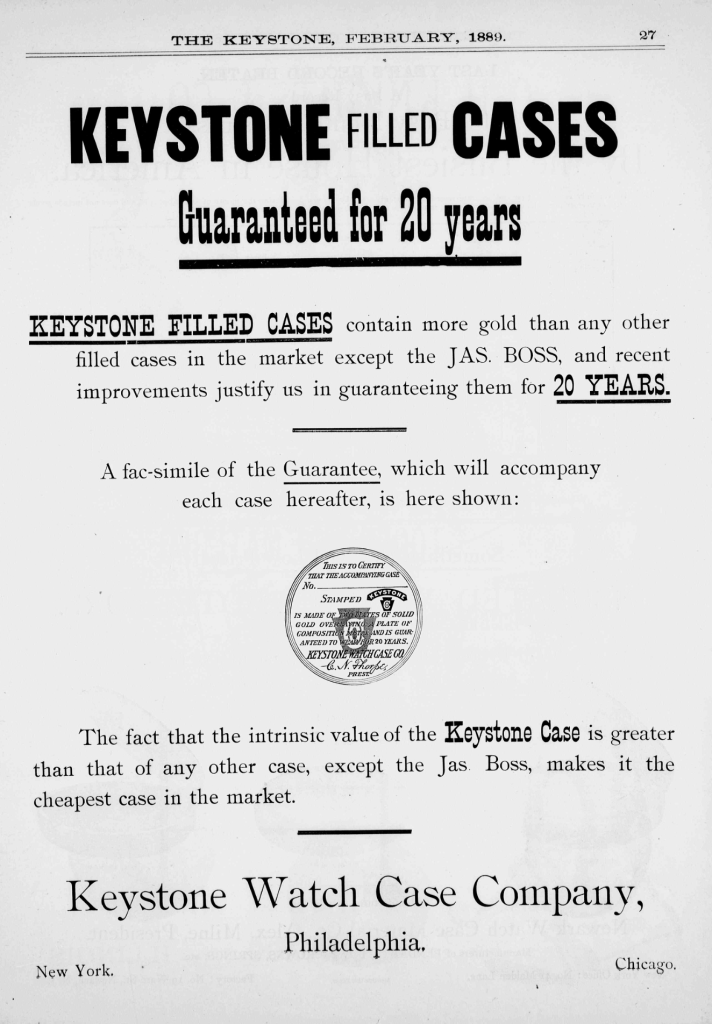

14K gold-filled cases were often guaranteed for a duration of 25 or 20 years. These cases were generally manufactured with thicker gold stock sheets and would remain durable for a longer period. 10K gold-filled cases were typically guaranteed for 10 or 20 years and were produced with a thinner layer of gold stock.

The Keystone, February 1889

While reputable companies made an appropriate effort to offer cases that would meet or exceed the stated guarantees, this standard was sometimes exploited by dishonest case companies looking to take advantage of the system.

Due to the lack of stricter regulation, dishonest companies could easily manufacture cases with thinner gold layers and stamp them with a premium-level guarantee. These cases would wear quicker than the stated warranty. And, because these deceptive companies would often omit the company identification, it was more difficult for customers to claim replacement cases through the warranty.

This became such a problem for the industry that the reputable case companies decided it would be advantageous to abolish the year-based guarantees, leaning more on the gold content and the case composition.

In 1923, several major case companies joined together to petition the Federal Trade Commission to outlaw all year-based guarantees on watch cases to weed out unscrupulous case manufacturers.

On January 18, 1923, the FTC convened the trade-practice submittal from the watch case companies, with Commissioner John F. Murdock conducting the submittal.

The Federal Trade Commission found that the complaints were valid and adopted a ban to address the concerns of the deceptive practice. It is important to note this was not a law or statute passed by Congress. Rather, it was adopted as an unfair competitive practice and was therefore enforceable through Section 5 of the FTC Act.

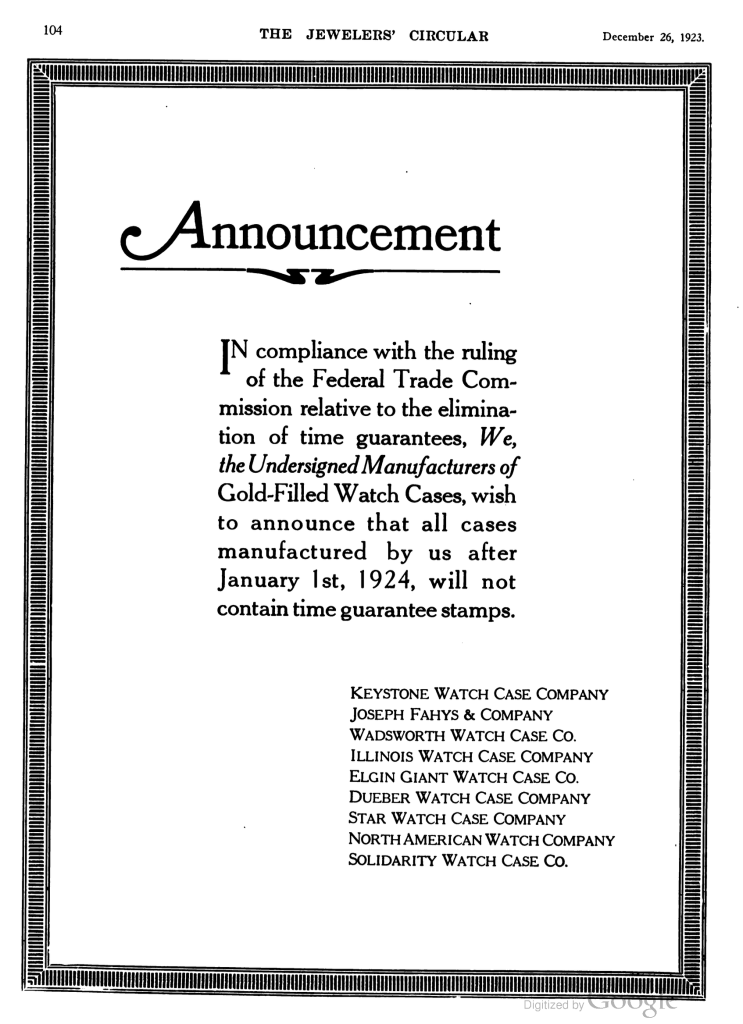

With the new trade practices being enforced by the FTC, several of the major American watch case companies published an advertisement in The Jewelers’ Circular announcing their intent that after January 1, 1924, year-based guarantees would no longer be used for watch cases. This applied additional pressure for the entire industry to comply with this new policy.

“Announcement – In compliance with the ruling of the Federal Trade Commission relative to the elimination of time guarantees, We the Undersigned Manufacturers of Gold-Filled Watch Cases, wish to announce that all cases manufactured by us after January 1st, 1924, will not contain time guarantee stamps.”

This advertisement was signed by the following companies:

Keystone Watch Case Company

Joseph Fahys & Company

Wadsworth Watch Case Company

Illinois Watch Case Company

Elgin Giant Watch Case Company

Dueber Watch Case Company

Star Watch Case Company

North American Watch Company

Solidarity Watch Case Company

Starting in 1924, the industry discontinued the familiar year-based guarantee, which had represented the quality of layered gold cases. This move forced dishonest case companies to rely on promoting cases on their actual merits rather than inflated year guarantees.

This was also a strategic move for the major case companies to solidify their stronghold on the case industry in the United States. By prohibiting guarantees, the requirements to claim material as “gold-filled” became standardized. As a result, some lower-margin grades were discontinued, and overall gold usage may have shifted. The use of grade names to define quality for gold-filled and rolled gold plate cases began to wane as the standards started to direct the market.

In our next article, we will explore the specific regulations established by the FTC in 1924.