Stamping Out Deception: How Early Federal Laws and the 1906 National Stamping Act Transformed the American Watch Case Industry

Markings on watch cases in the United States were unregulated at the federal level until 1905. Unfortunately, this environment nurtured deceptive practices in the watch case industry. From debased solid gold cases to implied government certification, case companies benefited from being able to skirt around the edges of honesty to benefit their bottom line.

In 1904, The Jewelers’ Board of Trade from New York, the Manufacturing Jewelers’ & Silversmiths’ Association. (MJSA), and retail-jeweler state associations lobbied for a national law to address the misleading practice of stamping “U.S. Assay” on gold jewelry, including watch cases.

On February 21, 1905, Congress passed a law prohibiting the stamping of “United States Assay” on gold products to prevent customers from believing these marks implied a guarantee by the U.S. Assay office. These marking practices caused problems in the market, especially when case companies continued to debase the gold content under the stamped purity mark slightly.

“CHAP. 720.—An Act To prevent the use of devices calculated to convey the impression that the United States Government certifies to the quality of gold or silver used in the arts.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That it shall be unlawful for any person, partnership, association, or corporation engaged in commerce among the several States, Territories, District of Columbia, and possessions of the United States, or with any foreign country, to stamp any gold, silver, or goods manufactured therefrom, and which are intended and used in such commerce, with the words “United States assay,” or with any words, phrases, or devices calculated to convey the impression that the United States Government has certified to the fineness or quality of such gold or silver, or of the gold or silver contained in any of the goods manufactured therefrom. Each and every such stamp shall constitute a separate offense.”Act of Feb. 21, 1905, ch. 720, 33 Stat. 732 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §§ 291–292), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-33/pdf/STATUTE-33-Pg732.pdf.

After the act was passed, case companies in the United States quickly terminated the use of such marks. As a result, we can safely date any American gold case with “U.S. Assay” markings to before c.1905.

Despite the law being approved by Congress, there were still problems with misleading marking habits practiced on jewelry, including watch cases. Many leading associations in the jewelry industry lobbied for tighter regulation on marking practices to address unscrupulous manufacturers that were exploiting the lack of proper regulation.

On June 13, 1906, Congress passed a law to establish a national standard for truthful purity markings. The National Gold & Silver Stamping Act was a comprehensive reform that required honest markings, specifying tolerances allowed compared to the purity marking on items. While the bill covers all articles of jewelry, we will focus on the aspects affecting the watch case industry.

Source: Act of June 13 1906, ch. 3289, 34 Stat. 260–262 (National Gold & Silver Stamping Act), available at https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/uscode/uscode1958-00301/uscode1958-003015008/uscode1958-003015008.pdf.

- Gold articles (§ 2)

- General tolerance for most gold articles (excluding watch cases and flatware): ≤ 0.5 karat below the stamped fineness on a solder-free test piece.

- Watch Cases: stricter 0.003 (3 ppt) tolerance (~0.07k on a 24k scale). Market Implication: For the watch industry, this prohibited the practice of marking a case with “18” when the actual purity was debased to 16k or 17k.

- Whole-article (including solder) assay: ≤ 1 karat below the mark. To determine compliance, the assayer would remove other parts and test only the gold alloy in the case body, cover, bezel, pendant, and bow (plus any solder).

- Silver articles (§ 3)

- General tolerance: ≤ 0.004 (4 ppt) below the mark.

- “Sterling” = 0.925 fine; “Coin” = 0.900 fine, each with the same 0.004 tolerance.

- Whole-article assay (incl. solder): ≤ 0.010 (10 ppt) below the mark.

- Plated / gold-filled goods (§ 4)

- A karat or purity mark cannot appear unless the words “gold-filled,” “rolled gold plate,” “electroplate,” etc., are shown with equal prominence. Market Implication: Stamping a purity mark such as “14K” or “18K” became illegal unless the mark plainly indicated “that the article or part of the article is plated.” For this reason, marks like the one stamped on the Fahys Monarch cases with “14K” in the late 1890s were outlawed even though Fahys had already discontinued the mark.

- Using “sterling” or “coin” on plated silver goods is prohibited.

The bill applied to all goods made after June 13, 1907, exchanged in interstate or foreign commerce. The penalty for violation was classified as a misdemeanor, punishable by up to a $500 fine or up to three months imprisonment or both.

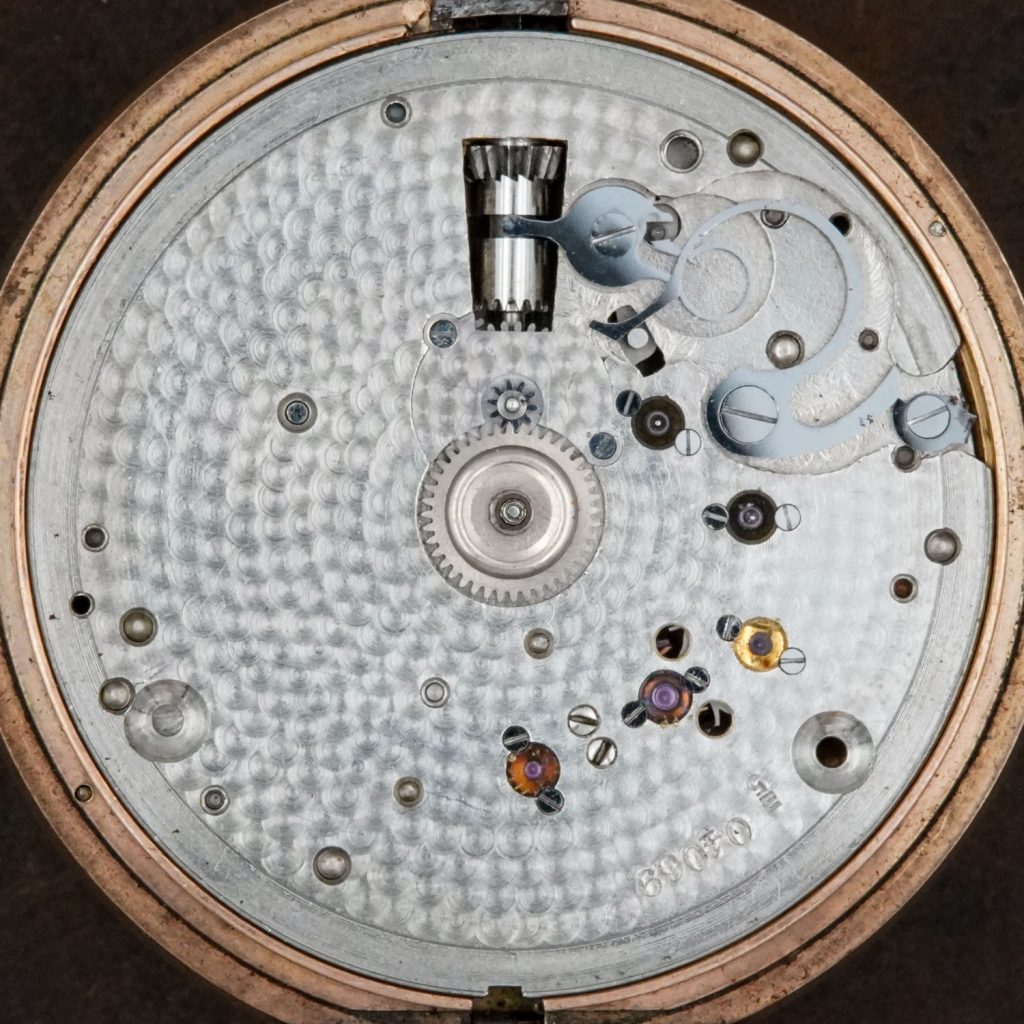

The bill was widely supported and welcomed in the industry as it leveled the playing field for honest manufacturers. By 1907, markings on watch cases had evolved to meet the new standards, and some case grades were discontinued – likely due to the inability to adhere to the new standards within a competitive market.

Companies like the Keystone Watch Case Company began marking some cases with a purity mark and case type, and solid gold cases were marked with more reliable fineness indicators. Other companies simply omitted karat fineness from case markings so they would risk violating the new laws.

Watch Case Dating Hints

For modern watch collectors, understanding the timeline of these federal laws can provide insight into extrapolating an estimated date from a watch case based on markings.

- If the case is marked “U.S. Assay”: Before 1905

- If the case is marked with a purity mark but not case composition: Before 1907

- If the case is marked with a purity mark AND composition: Likely After 1907

- Bonus Hint: If the case is marked with a year-based guarantee: Before 1924

Great article. I learned something except how do you date a watch case? I usually don’t care about gold or silver as the nickel/copper/zinc cases polish up beautifully. As nickel was a better material than gold and silver is its tolerance to temperature changes and it’s a far more durable material than any other metal used. And let me add that nickel is a semi-precious metal and was used abundantly more than gold, gold filled, and silver cases. I always start out disbelieving anything the case companies stamped on their cases. The serial numbers indicate more information along with the manufacturer’s name than any other marking. It would drive me nuts trying to find any information leading to the identity as to purities just armed with just those two criteria. I love my silver cases more than most not because of purity but because silver alloys make a nice case. Gold is a minefield and I don’t believe any of them regarding purity. As long as the case still has life left in them I will simply clean the case as best I can without dropping them into an ultrasonic cleaner that strips the lubricant or what’s left of a lubricant from the Pendents leaving them without any lubricant left. I’m building a grease gun for this very problem. Because everything is microscopic, tools are no different. I’m very dissatisfied that most every case has a serious problem with something whether it be the filth and grime stuffed into ever crevice, corner, and, well the entire case. I haven’t found one case yet that’s actually clean. I use Bergeon 1 or 2 micron cleaning paper to scrub ever part I can reach with the paper. Every case is phenomenally filthy. Sometimes I’m astonished to see people handle probable tetanus, cholera, polio, small pox, who knows but each person that holds one of these cases leaves fingerprints and dirt and oils from tens, hundreds, thousands of people who touched the watch. I don’t believe in a patina on my watch cases. It’s nothing more than corrosion. Nickel doesn’t corrode except for when the base metal is exposed to oxygen it forms a corrosive layer that protects the metal. That’s what I want my watches to look like. Like they were new. There are many more details to ask about but I know enough about metals especially the semi-precious metals used to make these wonderful machines that this knowledge keeps me out of trouble. Gold is a gamblers game as to purity. I’ve owned lots of gold of varying degrees of purity and know enough to stay away from investment gold watch cases as I believe they all cheated. People were more dishonest back then and they never washed their hands. Disgusting. But I’m an Elgin Watchkeeper and their materials I trust because it’s evident when I exercise my watches and a 155 year old machine built with tolerances to the ten thousandths of an inch kicks into gear and snaps back to life and will run it as long as I wind it. And it’s impossible today to test the accuracy without a Timegrapher. I use mine to set the watches but more interestingly is how the watch performs. And those ticks can be all over the screen with some watches struggling to operate covered in the same grime that’s on most of these watches all cause by mouthbreathers gawking at how pretty the movements really are and train soot and soot from every household in every city: remember that all lighting back then was still firelight. I can look at a movement now just by a picture whether or not the watch is clean. To choose wisely on eBay is a crap shoot. I’ve got masterpieces to the working man’s watch to watches that they call a parts machine but I call it a movement in need of repair. Unfortunately it takes a microscope to inspect the Jewel bearings so all I can do there is use the right loupe magnification. This is all very complicated especially when you factor in all the numbering systems that were used way back then for parts and even the serial numbers which is everything to enable tracking of the object. I could go on all day about which case company was better than another but that’s it for now. Something needs to be done. A modern rating system for a watch and establish parameters for testing of functionality and construction so buyers don’t get cheated by the statements made by sellers. Thank you for your time. PG