American Innovation: Merritt Burt’s Safety Pinion: Inside America’s First Patented Safety Pinion (Part 2)

On September 13, 1864, Merritt Burt was granted the first patent for a safety pinion design in the United States.

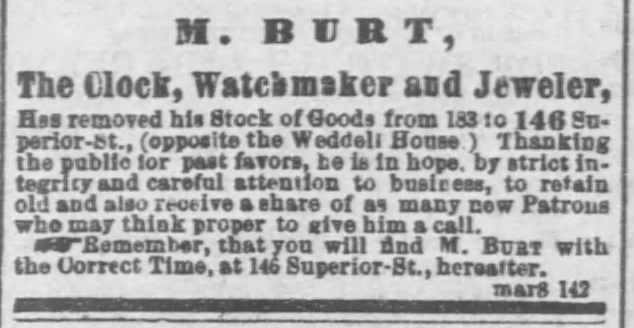

At the time of the patent, Merritt Burt was a skilled watchmaker operating a successful jewelry store in Cleveland, Ohio.

The Cleveland Leader and Morning Herald

Cleveland, Ohio

Wed, Mar 16, 1864

The primary objective of a safety pinion is to save the delicate watch parts from the sudden and destructive force that occurs when a mainspring breaks. Burt’s safety pinion design was adopted by the National Watch Company (Elgin) shortly after the company was organized and included in watches sold from the company’s market introduction in 1867 until approximately 1871.

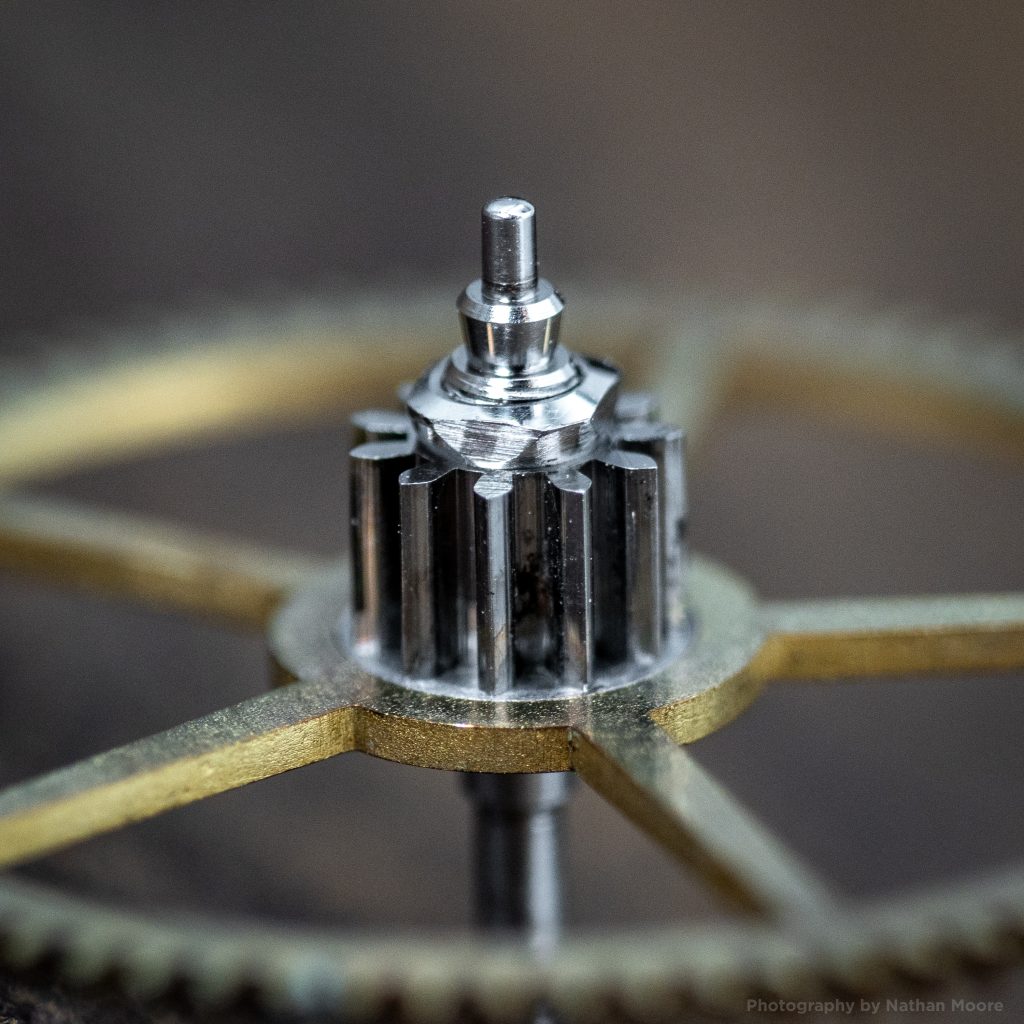

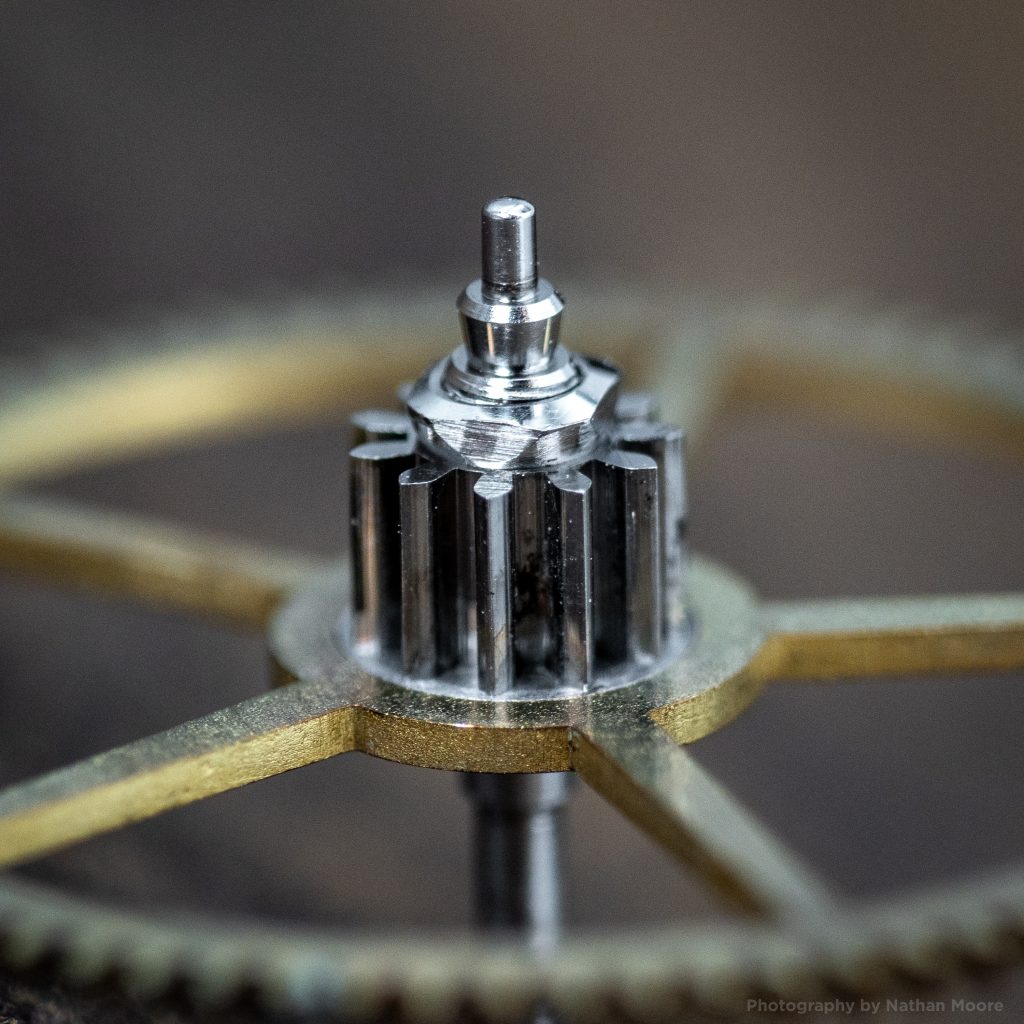

A Closer Look At The First Patented Safety Pinion in America

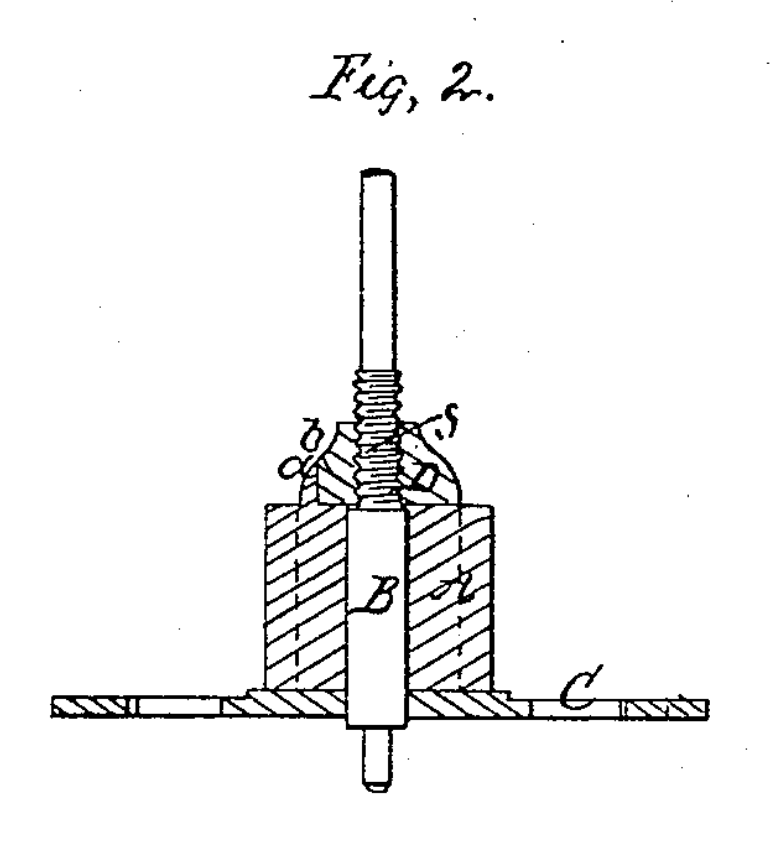

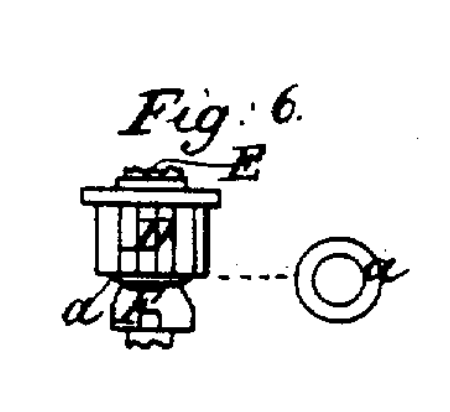

Merritt Burt’s design consisted of a threaded arbor on the center wheel to allow the tightening of a nut on top of a hollowed center pinion. Without the nut in place, the center pinion could rotate freely around the arbor. However, when the nut was substantially tightened, the pinion was secured for standard operation. When the mainspring inevitably broke, the force would be expelled from the barrel to the center pinion in the opposite direction. As a result, the friction between the pinion and the nut would immediately unscrew the nut, allowing the pinion to spin freely on the arbor until the force was entirely expended.

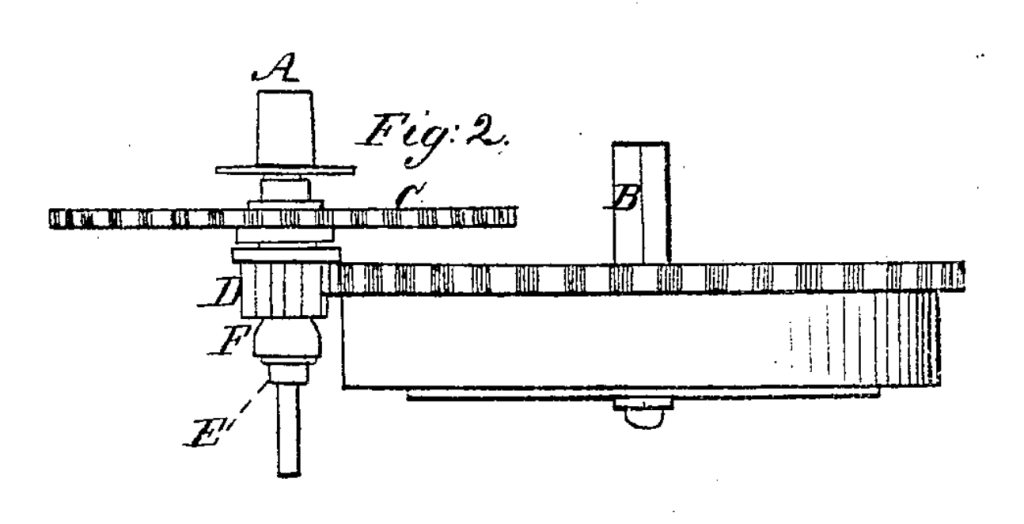

The Patent

Burt described his invention in the patent application:

“The operation is as follows: When the watch is in motion as a time-keeper, the pinion D, shaft E, and wheel C rotate in concert.

In the ordinary winding of the watch the pinion D does not turn upon the shaft E, but if the winding is continued beyond the limits of the spring the pinion is caused to turn upon the shaft, thus relieving the teeth from an unnatural strain; and in case the mainspring should break while the watch as in motion, the pinion D would turn upon the shaft E, and thus save the teeth of the wheels from being broken. My improvement, therefore, relates to devices for preventing injury to the train or the usual bad effects which result from the sudden recoil of the mainspring in case of its rupture when wound or partly wound up with too much force. The pinion D will turn in either direction upon the shaft E without entire disconnection with the train.” Merritt Burt, U.S. Patent #44161

One key aspect of Burt’s design that differs from other safety pinions in development at the time is that the pinion was intentionally constructed to not only save the train from sudden shock but also relieve excessive pressure if the watch was wound too tightly. Unfortunately, the provisions for both features ultimately led to the pinion being unreliable, often unintentionally slipping in certain scenarios.

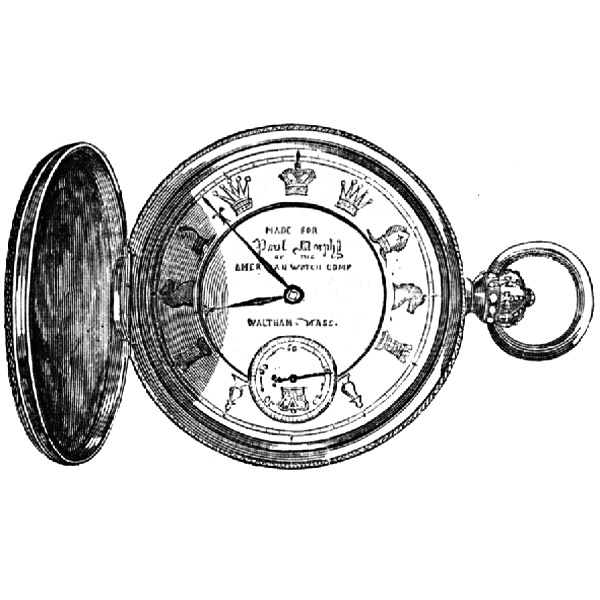

Identifying Watches Fit With Burt’s Patent Safety Pinion

Early B.W. Raymond watches fitted with Burt’s Safety Pinion are marked “Burt’s Patent” on the top plate, directly under the regulator arm. Watches without this marking will require further inspection to determine the presence of Burt’s patented safety pinion.

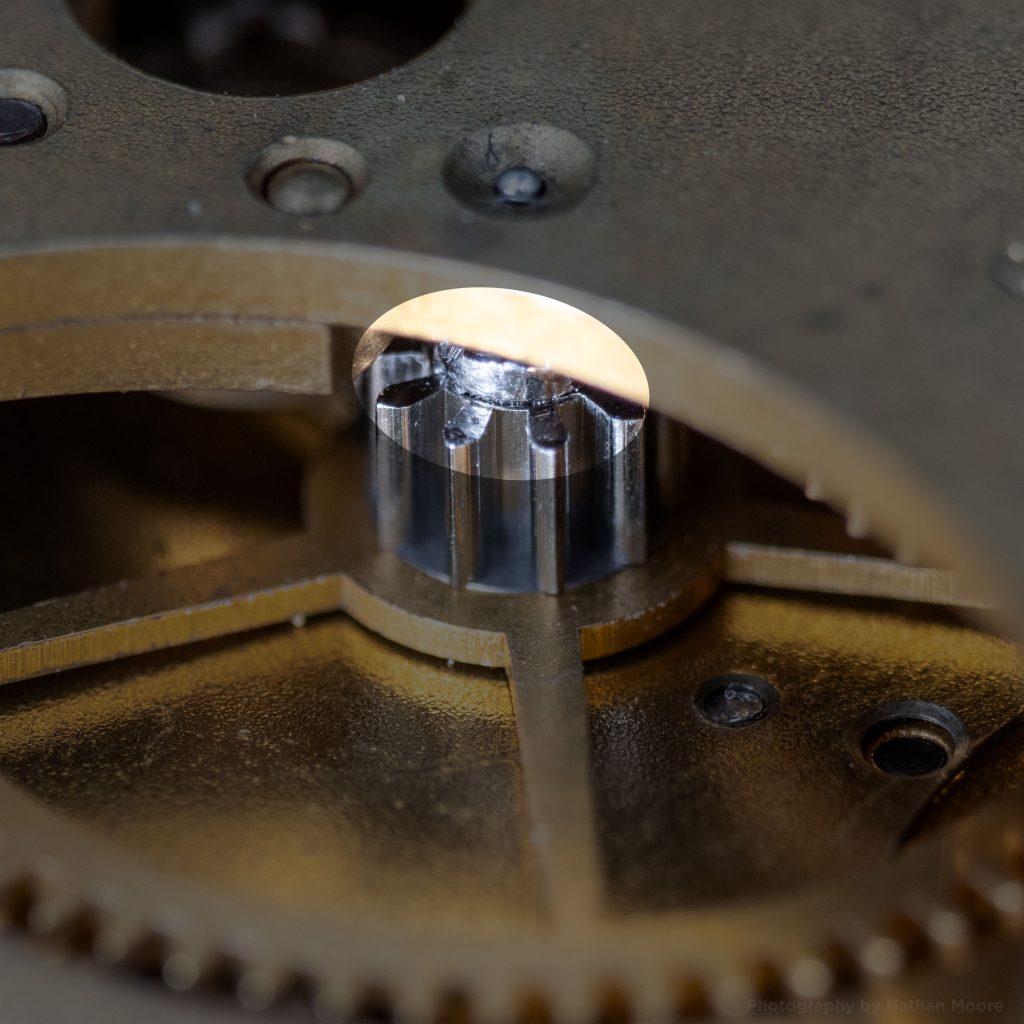

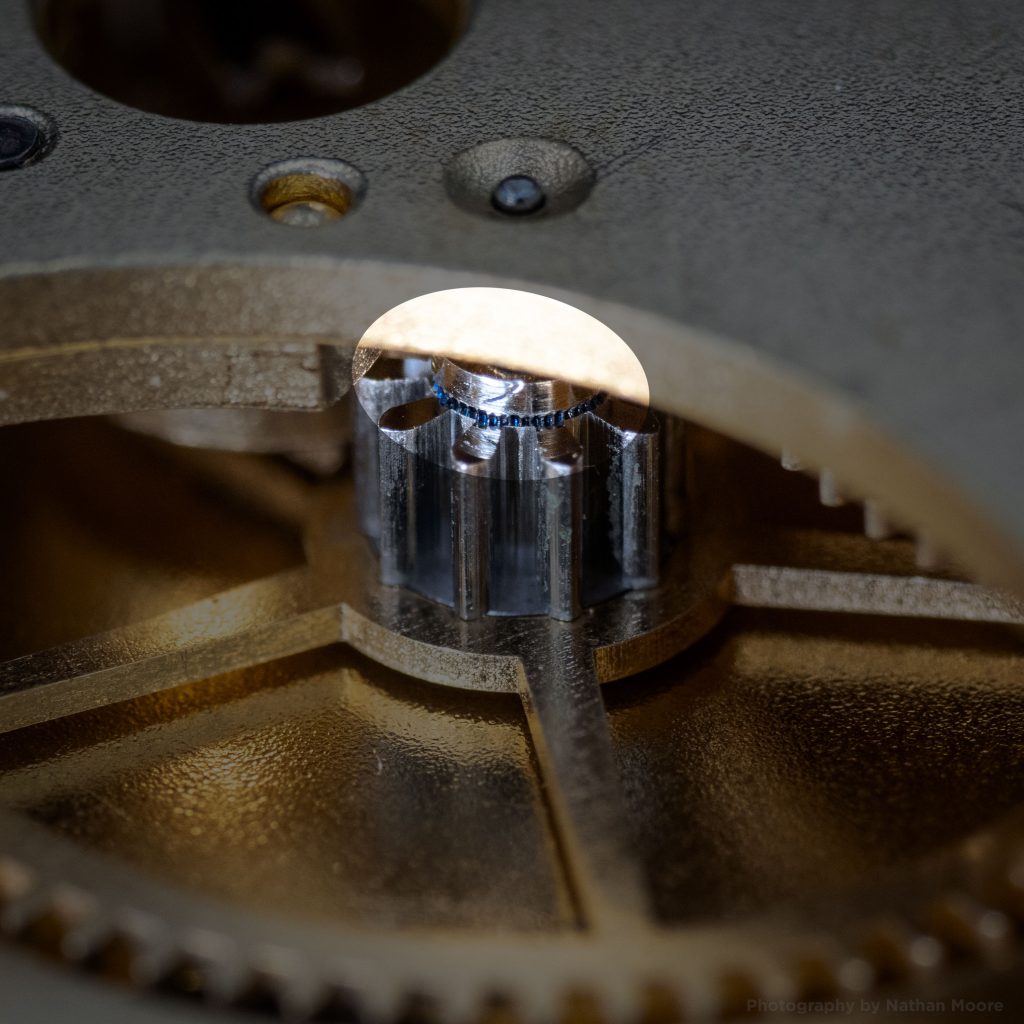

If the watch movement was manufactured at the Elgin factory before 1871, it was likely fitted with Burt’s safety pinion. A quick inspection of the center pinion once the barrel is removed will reveal a small nut on top of the larger center pinion. Usually, the threads on the center arbor will also be visible above the nut.

Elgin replaced Burt’s design with an improved design by Charles S. Moseley around 1871. Moseley’s design added several grooves that provided more friction between the nut and the pinion. If grooves are visible on top of the center pinion, the design should properly be attributed to Moseley instead of Burt. If no grooves are visible, it is likely Burt’s patent pinion.

The Spring Washer

Interestingly, the patent description also makes provisions for an option spring washer to improve the effectiveness of the nut on the center pinion:

“This friction may be increased or diminished by the adjustment of the nut F upon the shaft E. This adjustment and pressure may be increased in delicacy by interposing a concave washer between the nut and pinion. This washer, if made of very thin metal, acts as a spring, and would give a very nice adjustment of pressure. I do not, however, apprehend that this device would be generally needed.” Merritt Burt, U.S. Patent #44161

Burt received a reissued patent on March 6, 1866, which further illustrated this washer and, curiously, did not suggest it may not be necessary.

All examples I have studied were either not fitted with this spring washer or the spring washer was removed at some point in history (I imagine these would have been small and easy to misplace during service).

The Bacon Patent Pinion

By 1869, it was evident that Burt’s patent pinion was inherently flawed. It was critical that the nut was installed with a particular torque to be effective. If it remained too loose, the pinion would prematurely slip while the watch was being wound. If it was installed too tight, the pinion teeth would frequently break before the force could unscrew the nut during a mainspring event.

On November 16, 1869, a patent was issued to Benjamin Bacon for an improved design and assigned to the National Watch Company (Elgin). In the patent application, the faults of Burt’s patent pinion were directly identified:

“Should a person or a watchmaker be not perfectly well posted as to how tight the nut should be screwed up, he may screw it so tight that the back-action will not turn the nut, in which case the nut is of no avail whatever, the pinion then being liable to break by the back-action just as much as if there were no loose pinion. The pinoin might as well be fastened to the arbor, as to have a nut that is screwed so tight that it will not turn. With my improvement, the pinion will always turn when there is back-action.” Benajmin Bacon, U.S. Patent #96865

This was essentially an admission to the issues with Burt’s design. Bacon’s improvement was a small stud or pin that coupled the nut to the pinion. This prevented the pinion from unintentionally slipping but would have also eliminated the feature from Burt’s design that allowed the pinion to spin to relieve excessive pressure during winding. However, this was not a serious problem that required a solution. The effectiveness of the safety pinion in saving the watch when the mainspring broke was the paramount concern.

While it is possible Bacon’s patent safety pinion design was used in some production movements between c.1869 and c.1871, I have not seen a single surviving example with the Bacon pinion installed. Surprisingly, it appears that the company continued to utilize Burt’s design through c.1871, when it was replaced with an improved design created by Charles S. Moseley.

Although I am not a watchmaker, I own several pocket watches and really appreciate these articles.