The Illinois Watch Company Observatory in Springfield, Illinois: Timing Watches by the Stars

As watchmaking advanced in the 20th century, new methods were required to ensure precision and remain competitive in the market.

In 1910, the Elgin National Watch Company constructed a dedicated observatory to time and adjust watches using celestial positioning. In response, the Illinois Watch Company opened its own observatory in 1913 following the same principle.

The observatory project at the Illinois Watch Company was led by factory superintendent George F. Johnson. In addition to his work at the watch factory, Mr. Johnson was also an experienced astronomer, and his knowledge became vital to the success of the observatory.

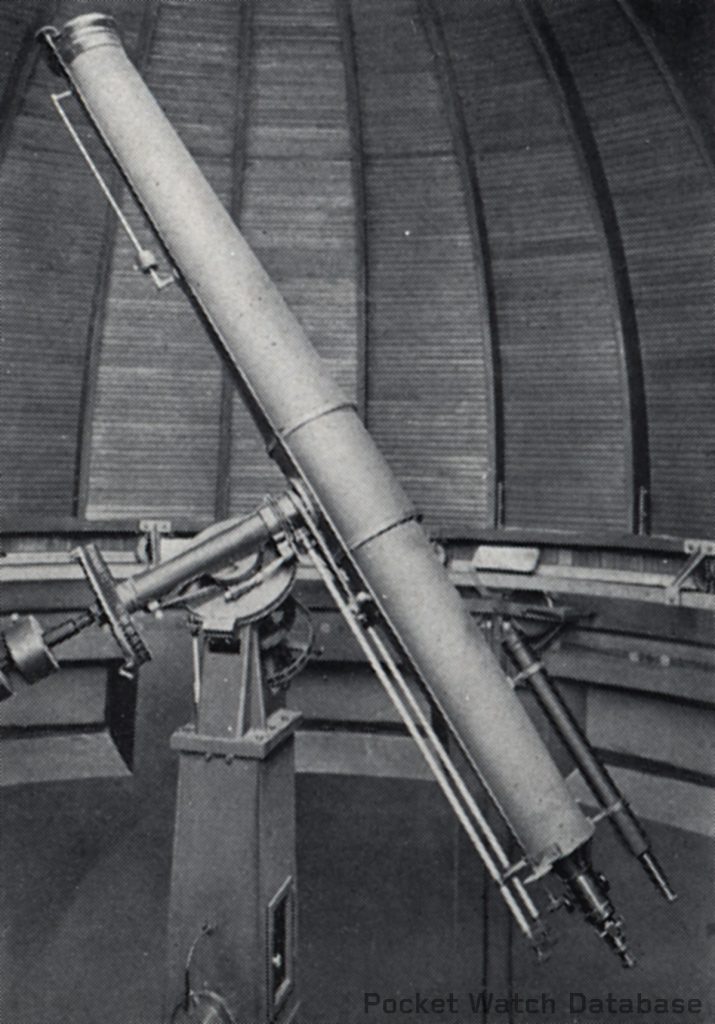

The two-story observatory was located near the factory at the corner of 9th and North Grand Avenue in Springfield, Illinois. The building was 25×50 feet and cost $14,000 to construct.

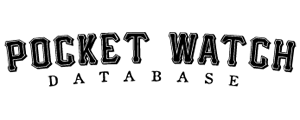

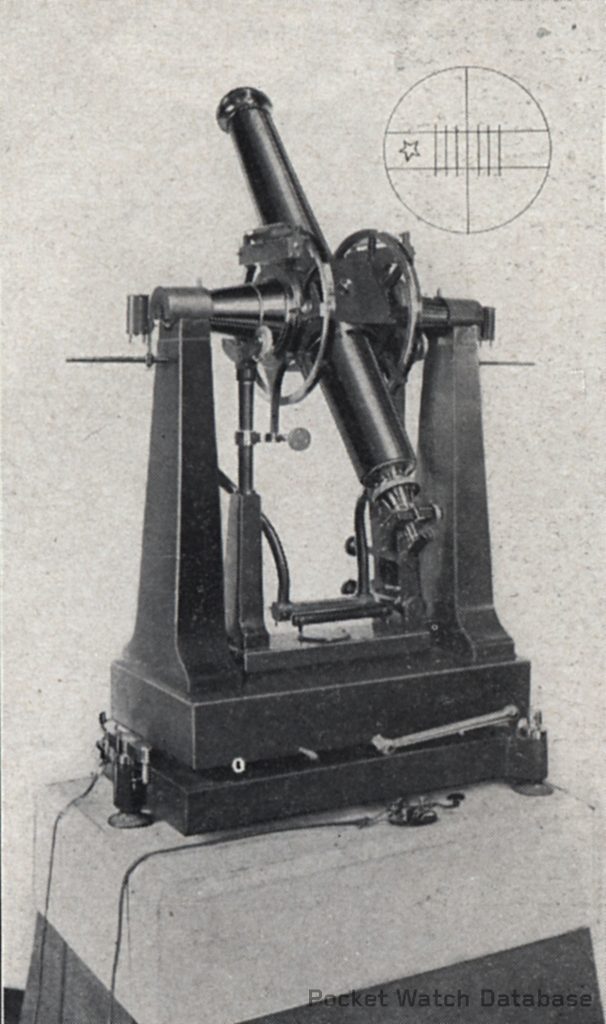

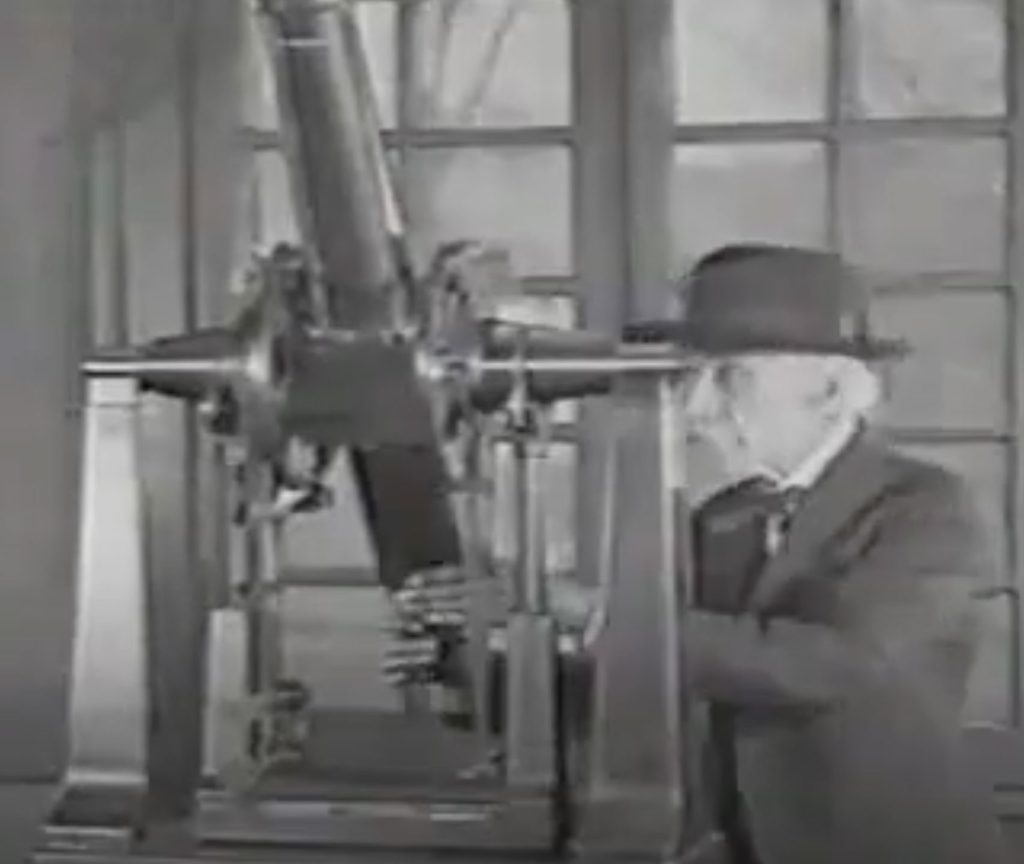

The observatory was equipped with two telescopes. The transit telescope, which was used for timekeeping, was created by Gaertner Scientific in Chicago. The larger 12-foot equatorial telescope was of Johnson’s own design and was constructed at the watch factory. This telescope was designated for public demonstrations and stargazing. The 8.5-inch lens was shaped by Petitdidier, an optician who specialized in optics for scientific equipment.

The railroad watches produced at the factory were timed using the transit telescope to observe the positioning of stars. The company claimed to achieve accuracy within one one-hundredth of a second.

A newspaper article published in the September 10, 1913 issue of The Springfield Evening News explained the process:

“In the lower rooms, the other astronomical instruments and wireless system will be located. In the beautiful east room, a $1,000 transit designed by the William Gaertner company of Chicago will be placed. Through the transit the exact time may be taken from the stars, and by the pressing of a button on a chronograph, the time of the watch factory clock at the same instant of star time may be set. With the new transit, the exact location of the city to a second of latitude may be found.

[…]

At the base of the dome in the new building is a large room in which is a vault within a vault, the last hermetically sealed by specially constructed doors. In this vault, where the temperature will always be the same, with the atmosphere dead, the clocks of the watch company will be kept behind a plate glass door. One is to be sidereal time, the other mean time. The sidereal or star time is four minutes faster than sun or mean time, but through the sun time the mean time may be found. With the facilities for observation of the stars, and the wireless service from Washington, the factory will have two checks on the correct time, a thing enjoyed by few factories.”

The observatory was also described in detail:

“The building is not only serviceable but a model of architecture. With no price spared on its construction, the completed works will cost many thousands of dollars. The exterior is of stone foundation, finished in tapestry brick and trimmed in white tiling.

Throughout the interior the hangings are the finest, while the beautiful frescoing of the rooms, makes the place look like a fine house. Upon the finishing of the wireless plant, a formal opening and reception is to be given. Astronomers from many of the colleges of the country have given ideas for the construction and they will be invited to be present.”

The company used the observatory in promotional materials, as shown on this postcard distributed around 1920.

In the 1921 publication Illinois Watches and Their Makers, the company further explained the methodology for timing watches by the stars:

“Time is a measure of duration. We reckon it in various ways. Take, for instance, a day. This is the time it takes the earth to rotate once on its axis. With reference to the sun, we call this rotation a solar day; with reference to any fixed star, a sidereal day. A year, consisting of 365¼ days, is the time it takes the earth to make one revolution in its orbit around the sun.

The first motion of the earth causes day and night; the second, the changing seasons. These revolutions, then, give us our idea of the passage of time. But the sun standard is not an accurate one. For six months of the year the sun is south of the equator, while during the other six months it is north of it. Twice in the year—at the equinoxes—the sun crosses the equator and we have days and nights of equal length. Twice in the same period the sun is farthest north and farthest south and we have the longest and shortest days of the year. Reference to a table of sun and clock time will show that on—

• February 10th sun time is 15 minutes slow.

• May 14th sun time is 4 minutes fast.

• July 25th sun time is 6 minutes slow.

• November 2nd sun time is 16 minutes fast.

In the earlier ages the sun time standard answered every purpose. But it is not sufficiently accurate for the age in which we live. We must have an unvarying standard—one that is absolutely the same on every point of the globe. That’s why we take our time from the stars. Now let us ascertain how this is done. First, examine this illustration of the trails of the stars in the vicinity of the North Star as they were photographed through a large telescope during an exposure of a little more than an hour. The North Star is not the pole of the heavens, but it is nearly in that position.

Note how the stars all seem to revolve around this point. They do this once in every twenty-four hours. This, then, becomes the earth’s standard for accurate time and is the basis of time measurements at all astronomical observatories. The one most familiar to us is located at Greenwich, England, where the true sidereal or star time is calculated from the host of fixed stars which cross that meridian.

The time each star crosses the meridian of Greenwich is recorded in a volume called “The Ephemeris” and can be obtained by astronomers everywhere.

Longitude is reckoned from Greenwich and its meridian is marked zero. Springfield’s longitude is 89° 38’ 33”, or nearly 90° west. As there is a difference of one hour in time for points every 15 degrees east or west of Greenwich, our Central Standard Time is 6 hours earlier than Greenwich. The exact time on our meridian given above is 5 hours, 58 minutes and 34.2 seconds earlier than Greenwich. All that is needed, then, to determine local time is to observe the passage of any of the fixed stars over the meridian of Springfield and to note the time of crossing by a Sidereal Clock. The object of the star observation is to determine the error of the Sidereal Clock. This done, the error of the Mean Time Clock is easily found by a simple formula which reduces Mean Time to Sidereal Time.

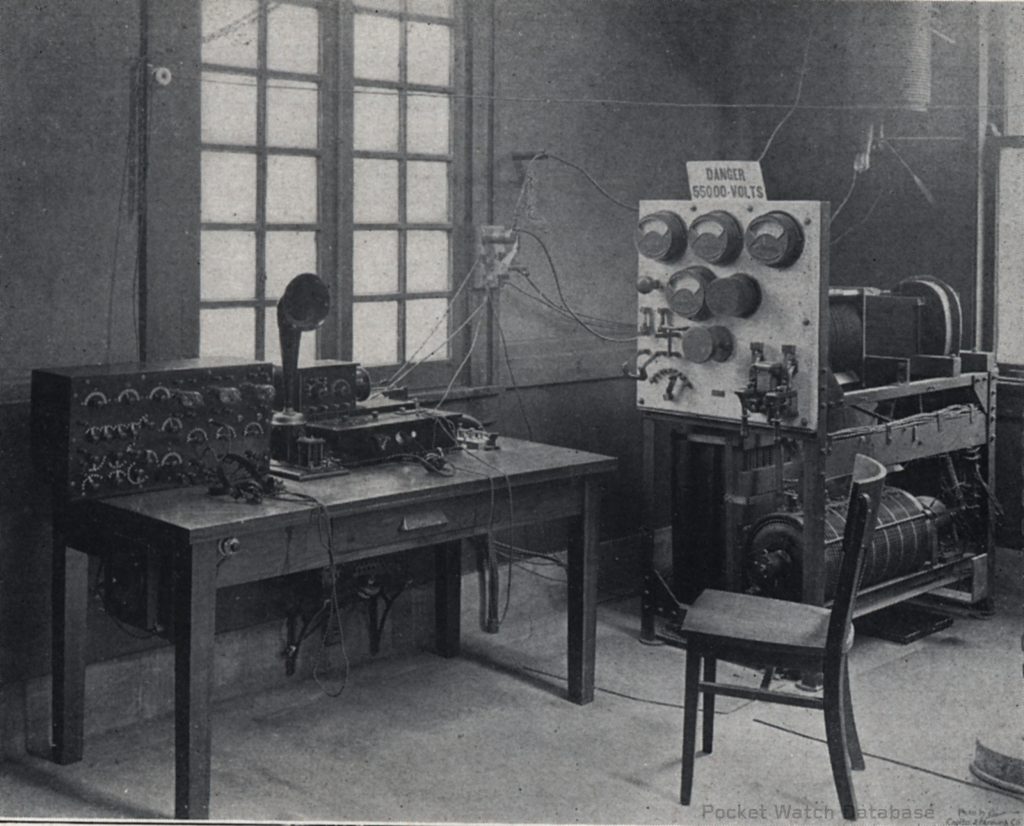

These observations are made through a transit, a small telescope set in the east room of the observatory. This instrument swings on the meridian and can be directed toward any star which crosses it, whether north, south or overhead, as the observatory was built with openings for this purpose.

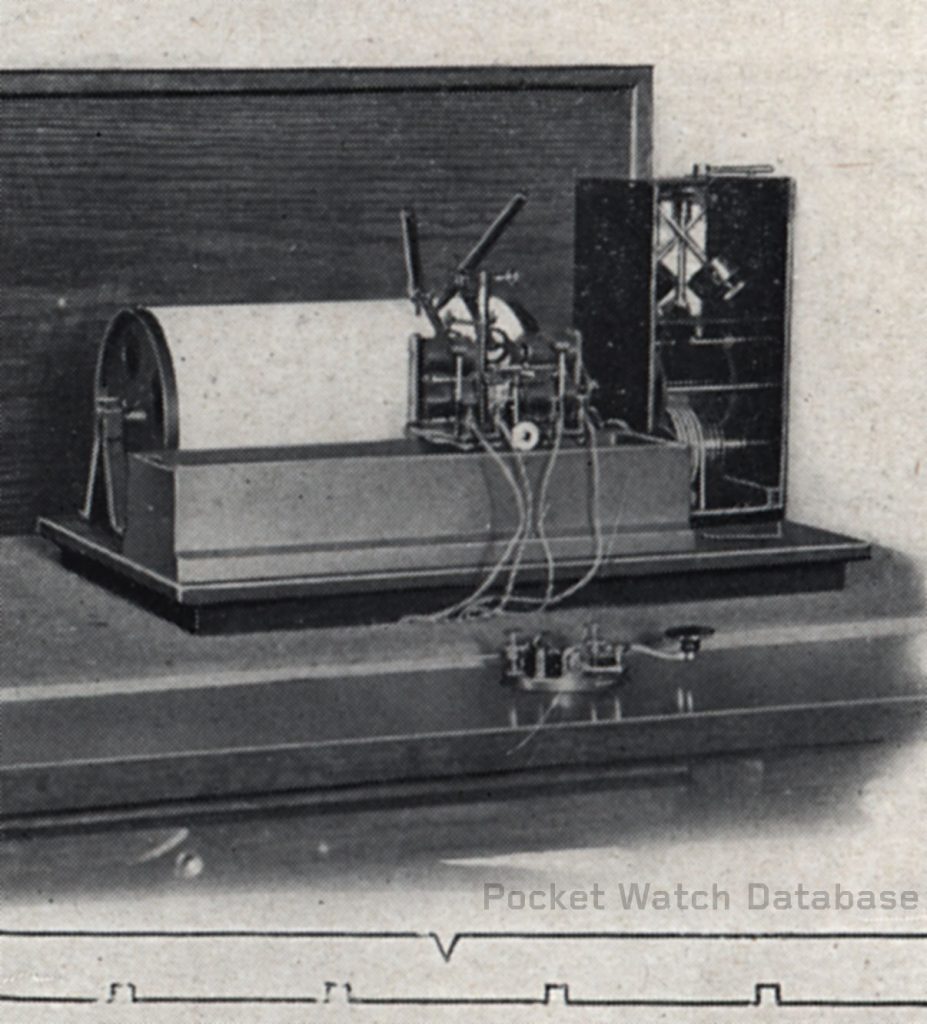

In the eyepiece of the transit we find a series of vertical spider lines, as well as several horizontal ones. The observer turns the telescope to the altitude where the particular star he has in mind will cross the meridian. As the star crosses the various spider lines he touches the key shown in the front of the instrument. This key is connected with the chronograph which records Sidereal Time by one pen while the other pen records the time of the star’s crossing of our meridian. Each span marked by these pens on the chronograph is a half inch in length and measures just a second of time. Each time the key is touched to record the crossing of a star the pen connected with the key “jumps.” When the observation is concluded, the space between the marks made by the Sidereal Clock pen and the observation pen are measured by a rule divided into hundredths of an inch. As each pen covers a half inch of space in a second, a difference of 1/100 of an inch between the “jumps” indicates that the Sidereal Clock is just 2/100 of a second fast or slow. These observations are taken daily and afford an unvarying standard by which our master clocks are kept regulated, and these in turn supply the standard which is so rigidly followed in adjusting and timing of “Illinois”—the world’s finest watches.”

Using observatories and telescopes for timing watches was a fruitful marketing strategy for watch companies like Illinois and Elgin. These observatories were also used to provide precise time to the town clocks in the area, so the watch company became the source of accurate time, further solidifying the perceived reliability of the watches created in the factories.

The observatory on the grounds of the Illinois Watch Company was deconstructed in 1938. The advanced transit telescope was acquired by Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois – the site of the original Peoria Watch Company factory. However, the telescope was never utilized by the university and was found and reassembled in 1955 at the Northmoor Observatory at Donovan Park in Peoria, where it is still in service.

Image Courtesy of Astronomical.org

To see the Illinois Watch Company observatory in action, including operation of both telescopes in the original building, check out this fantastic c.1922 film produced by the company: https://youtu.be/vTQT6PwgJTA?si=GsJqQKAKUjF2S8HW&t=2560