Guest Post: AWC Waltham Model 1870 “Crescent Street”

This post was originally published by Miquel Angel Cladera on his exceptional blog at SaFonaGastroCrono. The English translation has been provided by Google Translate with minor edits for proper clarification.

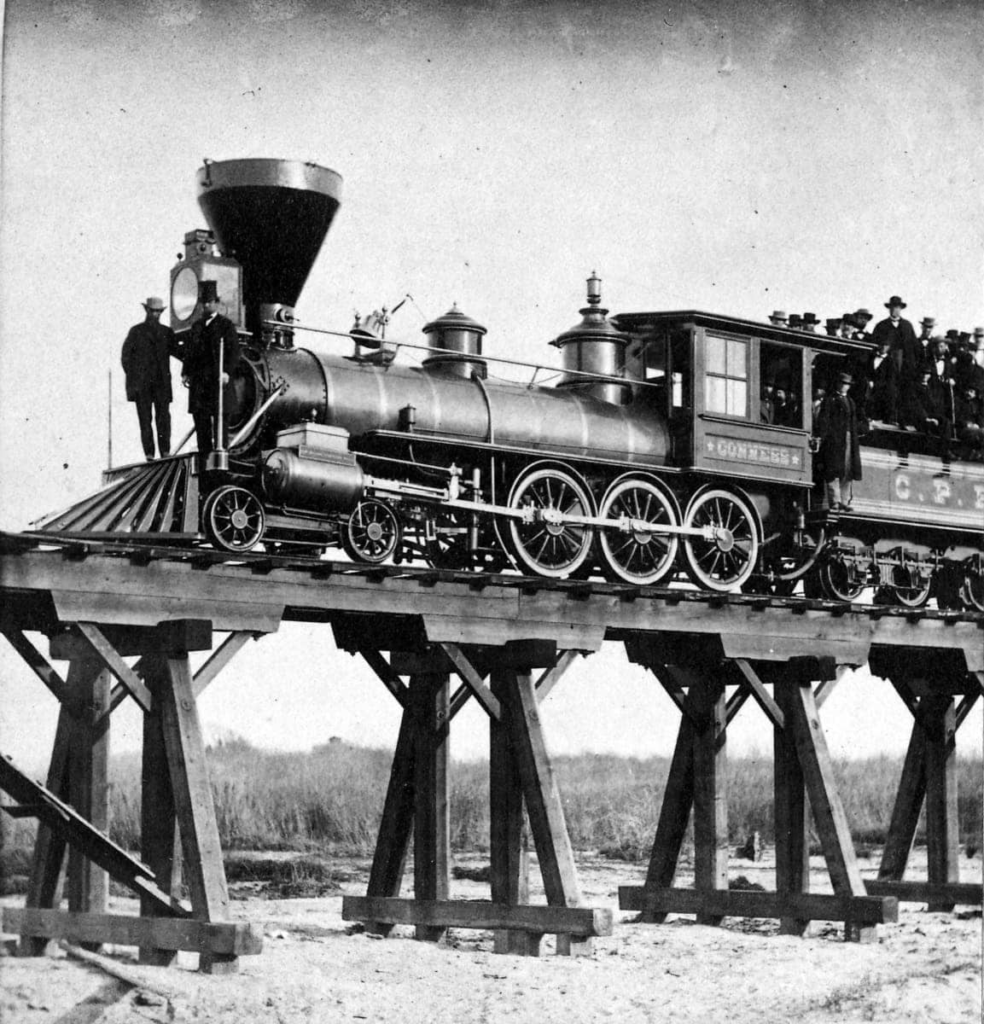

Throughout the entries that we have been presenting in our Railway section, we have been showing how the North American watch industry developed, largely motivated by the increase in roads and railways that were appearing throughout the country. This increase produced a true economic flourishing in all aspects of industry, speeding up and making more efficient communications between cities, the conquest of new territories, and the transport of goods and raw materials wherever they were needed.

As is evident, this entire railway organization needed a complex section of rules, regulations and labor to guarantee its complete operation; coming to establish different time zones in the continent and a standardized time, to try to have absolute control of it. The use of watches that were as accurate as possible by train drivers, engineers, mechanics and other train operators became essential. Today I would like to show you what is known as the first North American watch designed to be operated in the railway segment and as the title indicates, it is a watch manufactured by the American Watch Co., later known as the Waltham Watch Co.

Most experts and historians give it this creditable title, but was this watch really the first to be used on the railway? Was it the first to be designed for this purpose? Let’s see it. In August 1853, a fatal accident occurred between two trains of the Providence and Worcester Railroad due to the delay of a couple of minutes of one of them occupying the track of a crossing. This accident (the first to be photographed in a daguerreotype) cost the lives of 14 people in addition to causing a good list of injuries. Below we can see the same and a press release from the NY Times of the time.

This accident caused the railway companies, together with a national commission, to begin to legislate and establish regulations on the need to control time in the most exact and effective way possible to avoid this type of event. A regulation written in the same year of the accident, one of the oldest known, comes from the Boston & Providence Railroad, where it is formulated:

- A record will be made by the Ticket Clerk, or in his absence, by the Baggage Master, of the comparisons required by Art. 5 to which they will certify by their signature or initials.

- Drivers will submit their watches to Bond & Sons, 17 Congress Street, Boston, for examination, and procure from them a certificate of reliability which will be handed to the Superintendent.

- Drivers will report to Messrs. Bond any irregularity in the movements of their watches, and they will clean, repair and regulate them, at the expense of the Corporation, furnishing Conductors with reliable watches in the interim.

As we can see, the regulations still do not refer to how the watches should be and what characteristics they should meet to cover their performance well, but the purchase by the Vermont railroad of 15 watches of the English brand Barraud & Lunds through of the jeweler Bonds & Sons, who, as we have just seen above, were in charge of making sure the watches worked correctly. Fortunately, one of these copies is preserved in the Smithsonian and can give us a clear idea of the type of watches that began to be used in the main railway corporations.

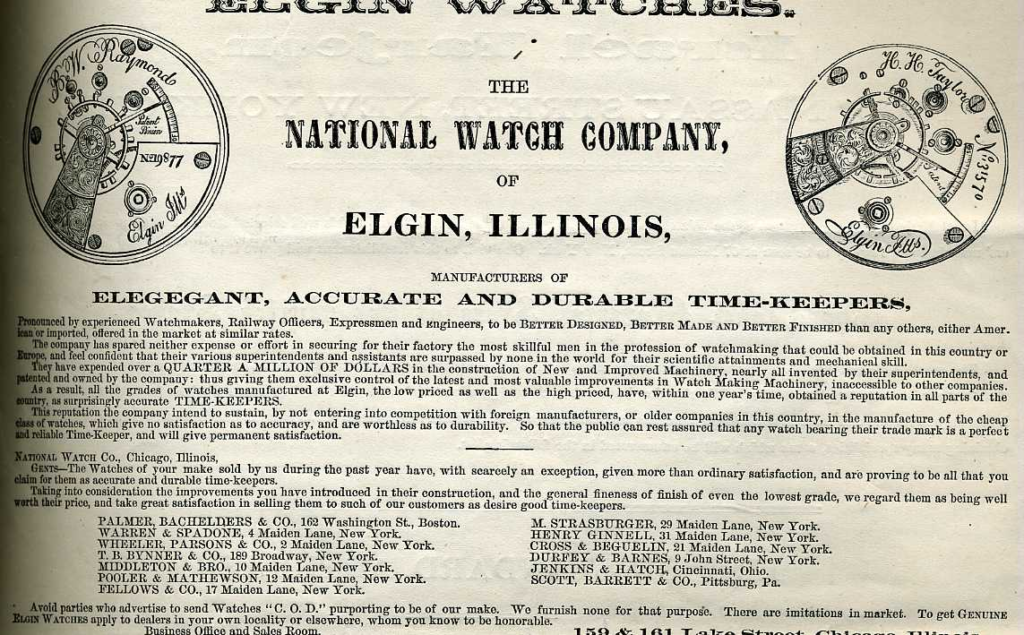

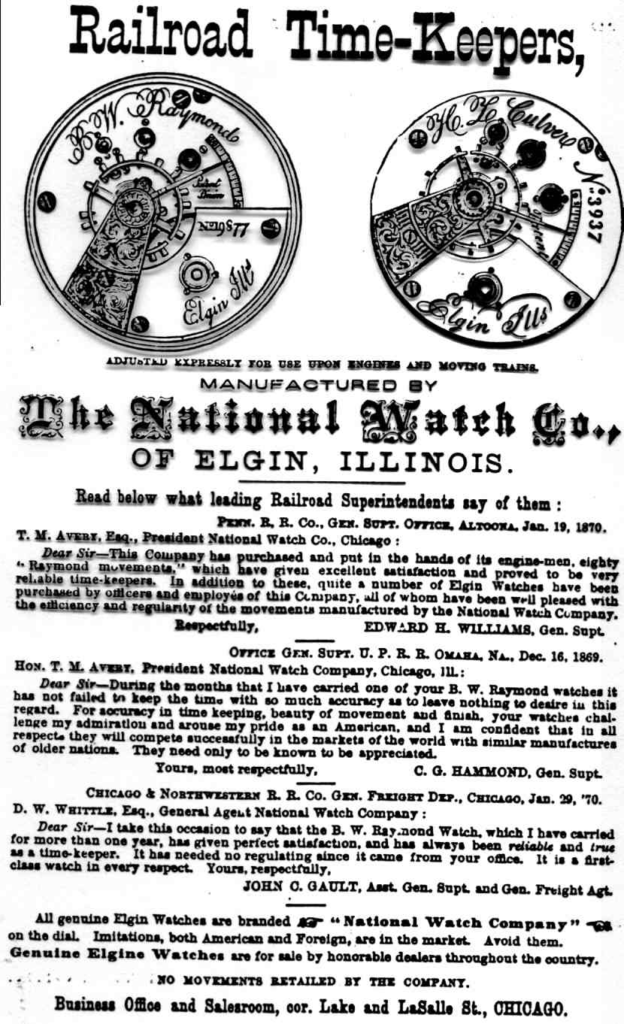

During that decade and the next, the American watch industry boomed and began to develop watches that were considered “suitable” for use on the railroad. New techniques for automating mass production of watches made it possible to create many units at cheaper prices than importing English watches. Thus, in 1866, it is documented that the American Watch Co. (AWC) provided 300 watches equipped with the caliber 1857 to the Pennsylvania Railroad. Only a year later a new start-up company, the National Watch Co., later known as Elgin, was commissioned to supply Grade 69 watches (as we saw in this post) .to the same Pennsylvania Railroad and of which a copy is also preserved in the aforementioned Smithsonian.

At this point, we see that before the appearance of our protagonist, the railroads already used North American watches, so we cannot attribute the authorship of being “the first American railway watch” to be used for this purpose. But was it the first designed exclusively for this segment? To answer well, we must examine its characteristics.

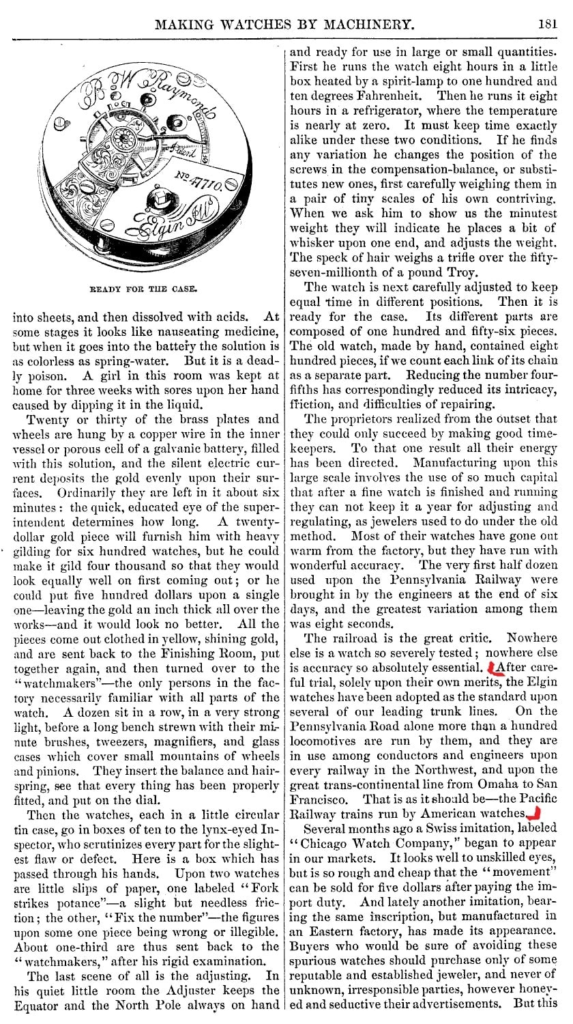

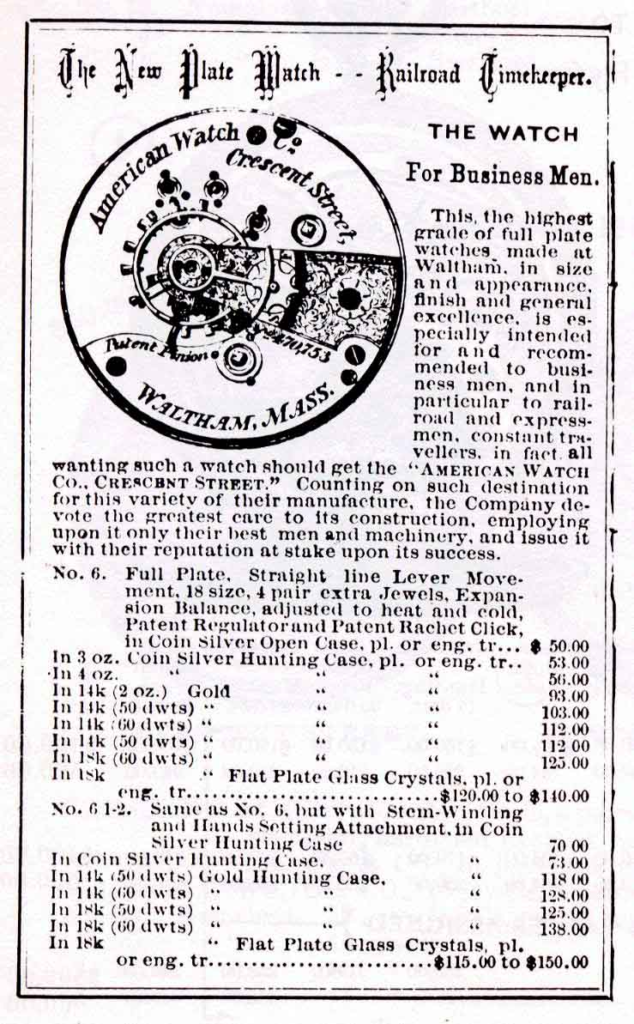

In the image above we can see its caliber in detail. If we start with its serial number, #520.083, we see that it is a copy made in 1870, the year in which it began its journey and which also gives its name to the model. According to existing databases, during its first year of life, almost 1,600 units were manufactured. The name of its degree “Crescent Street” comes from the address where the company was located and which is still preserved today as a museum and office building.

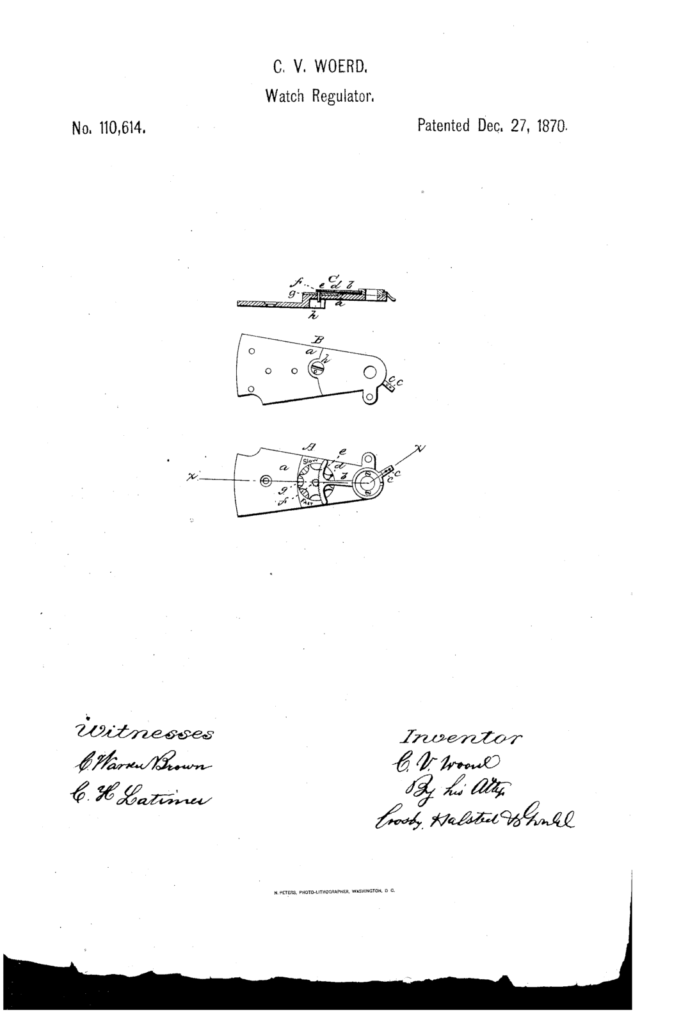

We can see that its plate is complete and the particularity is that it is adjusted and loaded from the back, something unusual in North American full plate calibers since this configuration was more common in English watches. Among the patents that make up this caliber, we can highlight the Fogg safety pinion, the inclusion of the Woerd micrometric regulator, a base plate where the barrel and a pawl were attached, as well as its main spring also designed by Woerd.

As can be inferred, most of the patents were the product of Charles Vander Woerd, the plant engineer for the Nashua Watch Co.. which had been absorbed by the AWC. The need to create a new caliber to replace the already “outdated” 1857 fell into the hands of Woerd. The American Watch Co. wanted to position itself in the railway segment with a new watch model that was compact and resistant, aware of the rattle of the trains, the variations in temperature and the accumulation of dust (effects that could vary the setting of the watch and even spoil it). The characteristics that this engineer gave it, together with an anti-dust ring, achieved the expected result. The new “Crescent street” grade, with its 15 jewels, adjusted to temperature, its compact plate configurations and the addition of the micrometric regulator, became the company’s “High Grade” to compete in the railway market.

Obviously, over time this caliber evolved and changed. Its evolution over time can be seen in the magnificent work of Mr. McIntyre. As we have seen, this new movement was developed expressly to work on the railway and was announced by the company (as we will see later) but was it really the first as claimed? My opinion is no. I do not want to be exhaustive in this and contradict the vast majority of fans and historians, but I think that the 1870 model was a response to the great watch that the National Watch Co. had launched on the market in 1867. About Grade 69 (BW Raymond) we already talked in this post And I’m not going to go into detail, but if we examine the two watches closely, we see that structurally they are very similar. Both provide shared construction solutions, including the anti-dust ring. Even the Raymond beats faster, 18,000 bph compared to the Crescent Street’s 16,200 bph. In my opinion, the great advantage of the AWC watch over the Raymond is that it can be set from the back without having to expose the dial, as is the case with the Grade 69.

Another favorable point for the new 1870 model is the inclusion of the micrometric regulator, something that favored and simplified its adjustment. In (approximately) 1871, Elgin engineers updated the Raymond, giving it its own micro-adjustment regulator (though, as we’ve seen, they didn’t patent it until 1874). We can see this in this unit from my private collection, dated 1871.

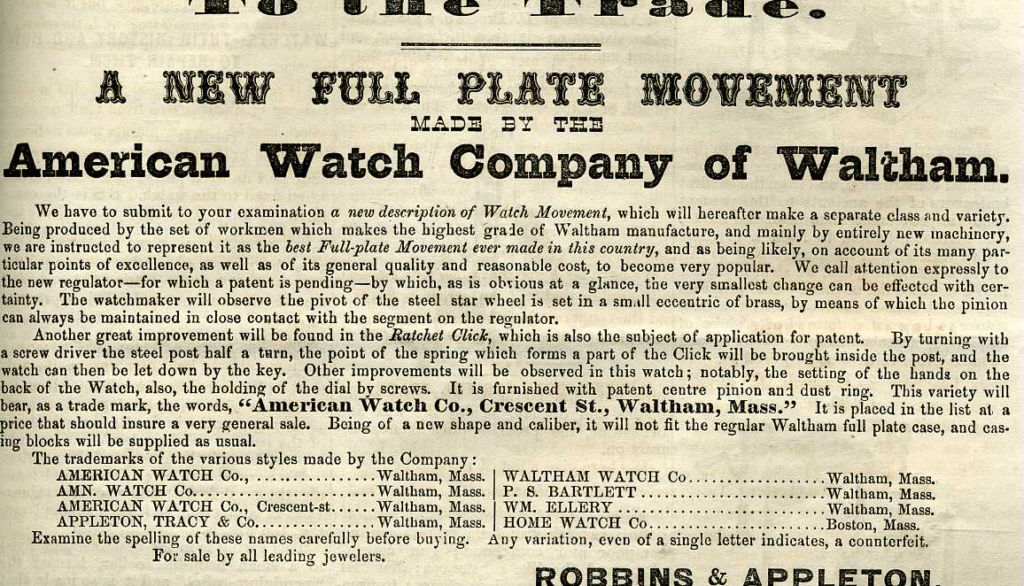

As we can see, one can disagree with the general opinion about whether the “Crescent Street” was the first watch designed to be used in the railway segment, although what is certain is that the AWC announced it that way (but only when it was already in the market). Below we can see what is considered to be the first known printed advertisement (1869) for this caliber.

This other one is also of interest, where one of the first watches produced appears, #470.753, and where it can be seen that it was not a cheap watch for the time (1870).

It is perhaps on this point that most researchers support the theory that the 1870 model was the first American watch announced specifically for the railway segment. I would not like to enter into more controversies, but there is also an ad from Elgin dated (circa) 1869/70, where he boasts of his experience in the railway sector, something truly true as we could see above for the purchase of watches by the Pennsylvania Railroad.

This one from 1869 appeared at Harper’s.

Or this other one, already from 1871, where, however, the referred opinions of the railway workers correspond to 1869/70.

The first announcement of the 1870 model was published in “The Watch Maker and Jeweler, Volume 1, Page 15” of September 1869, that is, four months before its launch on the market, as stated in his work Mr. McIntyre and that we have presented above. However, he makes no mention of the rail segment. Unfortunately, as I do not have access to the original archives, I am unable to decide whether the 1870 model or the Raymond was the first American watch announced to work on the railway, although my opinion favors the latter. It is important to mention that the engineers of the two companies had worked together years ago and therefore knew in advance the needs that a watch had to meet to meet the expectations of a railway worker, something that the watch companies skilfully exploited in the face of the substantial market that opened at their doors. Another important point that we have already seen at the beginning of this article is that of the railway regulation itself. A precise standardization on the characteristics that a railway watch had to satisfy. Be that as it may, both the “Crescent Street” and the “Raymond” marked the way forward in this regard.

A great article with lots of good information and research on these early railroad watches. The links provided were interesting also, particularly the one book, “The Evolution of Automatic Machinery as applied to the Manufacture of Watches” by E.A. Marsh (1896). Marsh was also an engineer who designed these machines himself. It makes a great little read itself.