Unhallmarked Nation: Gold Purity, Fraud, and the Road to Federal Gold Case Marking Standards

Unlike the robust hallmark system enforced in England, the United States did not begin regulating markings on precious metals at the federal level until 1905.

During the early decades of the American watch industry, each case maker maintained a set of marks to denote purity, often omitting an explicit mark to indicate gold purity, such as “14K” or “18K.”

The case marks applied during this era would typically lean on iconography mimicking the hallmarks seen in England, with embossed markings like a crown, lion, or eagle. Despite being widely used, these were private marks – not systematized by any common association or trade organization, to our knowledge. In fact, the crown was such a popular mark in Philadelphia, solid gold cases carrying a crown mark with no other identifying marks are notoriously difficult to properly attribute.

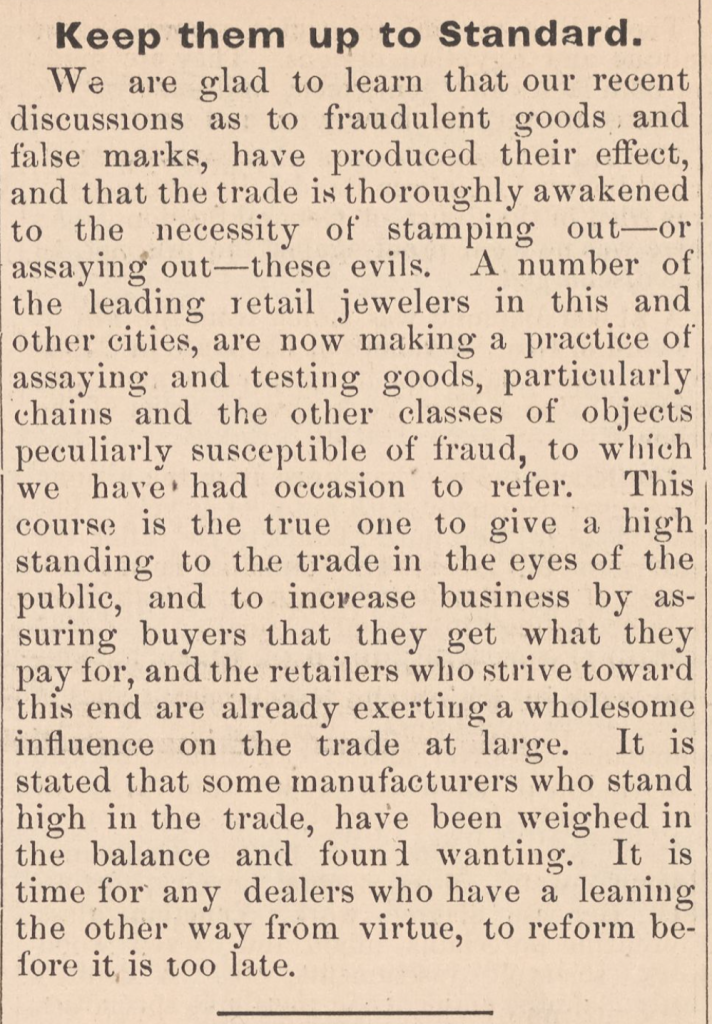

When a solid gold case did carry an explicit purity mark, it was sometimes overstated. The topic of debased gold was widely discussed as a serious problem in trade publications during the 1870s and 1880s. For example, a solid gold case marked to indicate 18K would only assay at 14 or 15K and a case marked as 14K would only assay at 10K-12K.

At the time, the lack of transparency in purity tolerances was heavily criticized, and many proposed a national system to regulate the purity marks. However, no action materialized from these proposals, and the market began to adapt, favoring case companies that practiced more transparency in marking habits.

State Regulations Begin

Since federal regulation was lacking, several states aimed to provide a framework to protect customers from fraudulent or misleading marks on gold cases.

1889: Connecticut

In 1889, Connecticut passed an act that outlawed the sale of any gold items with marks that improperly represent the actual purity. Offenders could be fined up to $1,000 or imprisoned for up to one year, or both.

“Sec. 53-325. Articles made of gold or alloy; false representations. Any manufacturer or dealer who makes for sale, sells or offers to sell or dispose of, or has in his possession with intent to sell or dispose of, any article constructed in part of gold or any alloy or imitation thereof, having thereon, or on any box, package, cover, wrapper or other thing enclosing or encasing such article or articles for sale, any stamp, brand, engraving, printed label, trademark, imprint or other mark, indicating or designed or intended to indicate that the gold, alloy or imitation thereof in such article or articles is different from or better than the actual kind and quality of such gold, alloy or imitation thereof, shall be fined not more than one thousand dollars or imprisoned not more than one year or both.” 2011 Connecticut Code, Title 53 Crimes, Chapter 946 Offenses Against Public Policy, Sec. 53-325. Articles made of gold or alloy; false representations.

1892: New York

In 1892, the state of New York followed with a similar law stipulating that any marks on gold items or packaging must be accurate within 1/2 of a karat of the actual gold purity.

1895: Massachusetts

In 1895, the state of Massachusetts became the third to outlaw misleading gold purity markings, requiring all purity marks to be within one karat of the actual fineness. Furthermore, the act also stipulated that the implied purity should represent the whole article – “all the gold, alloys, solder and base material being assayed as one piece, unless the work or mark plainly indicates that it applies to the plating, surface or other particular part of such article.” Under these guidelines, many gold-filled cases sold during this era could have been in violation of this law.

These state regulations did not require case manufacturers to apply markings to indicate purity. Rather, they outlawed suggesting or implying fineness that was not properly representative of the actual gold purity.

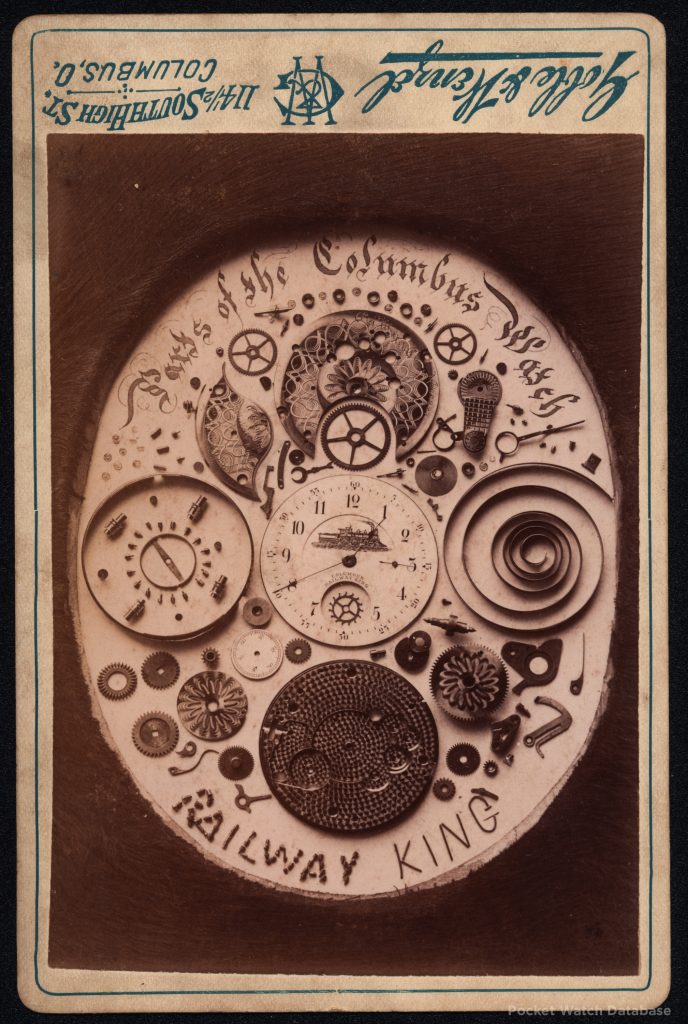

The “U.S. Assay” Markings

In the 1890s, the lack of proper federal governmental regulation prompted reputable companies to label warranties inside their watch cases to reinforce credibility. These marks inside solid gold cases were often accompanied by “U.S. Assay” to suggest backing guarantees from the U.S. Assay office. This strategy was successful, and soon, many leading watch case manufacturers were adding the assay warranties to their gold cases, although a few smaller makers and importers misapplied the legend. The assay guarantees became more about a loose indicator of quality rather than a strict measure for less reputable companies.

Image Courtesy of Jones & Horan Auctions

While the “U.S. Assay” marks implied testing and guarantee by the U.S. Assay office, it was uncommon for case companies to have gold samples actually tested by the U.S. Assay office. Instead, these assay tests would generally be handled internally and warranted based on the results.

Because customers frequently associated the “U.S. Assay” mark with a function of the government testing operation, the United States outlawed marks that suggested government certification in February 1905.

“§291. Stamping with words “United States assay”, etc., unlawful. It shall be unlawful for any person, partnership, association, or corporation engaged in commerce among the several States, Territories, District of Columbia, and possessions of the United States, or with any foreign country, to stamp any gold, silver, or goods manufactured therefrom, and which are intended and used in such commerce, with the words “United States assay”, or with any words, phrases, or devices calculated to convey the impression that the United States Government has certified to the fineness or quality of such gold or silver, or of the gold or silver contained in any of the goods manufactured therefrom. Each and every such stamp shall constitute a separate offense.” Feb. 21, 1905, ch. 720, §1, 33 Stat. 732.

General Tips for Identifying 19th-Century Gold Cases

Before c.1890s

Gold watch cases manufactured in 1850s-1880s typically carried ambiguous markings. When numerical marks were present, they would often overstate the gold purity or intentionally suggest a purity of 18K by adding an “18” marking while the purity was much less. For this reason, it is advised to not rely on case marks alone during this era. More reputable companies, such as the American Watch Company, Dueber, and Keystone, heavily relied on market credibility; therefore, the case marks used by these companies are generally more reliable. Cases marked with a company name or trademark are generally more credible than vague makers’ marks or anonymous manufacturers.

c.1890s-1900s

Gold cases manufactured during the 1890s and early 1900s typically carried more explicit markings, often warranted by the company to assay at a specific standard. However, while these marks are more reliable than the earlier ambiguous marks, they, too, have been found to be overstated. For this reason, it is advised to assume a slightly lower karat purity than what is represented on the case and test with a non-destructive method when prudent.

1906 and Beyond

After the National Gold & Silver Stamping Act of 1906, marks applied to cases were federally regulated more strictly, with specifications that any karat marking must be within 1/2 a karat of the actual material purity.